Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

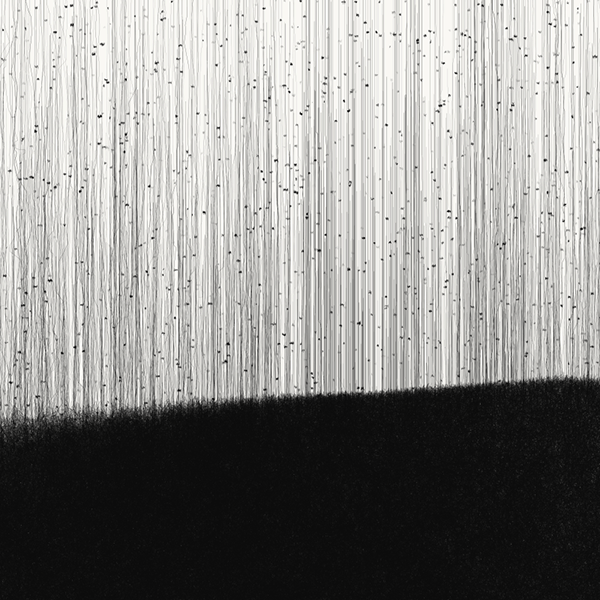

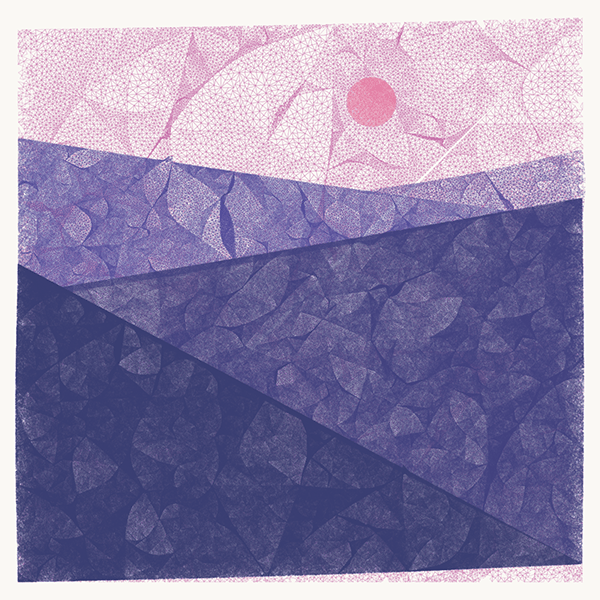

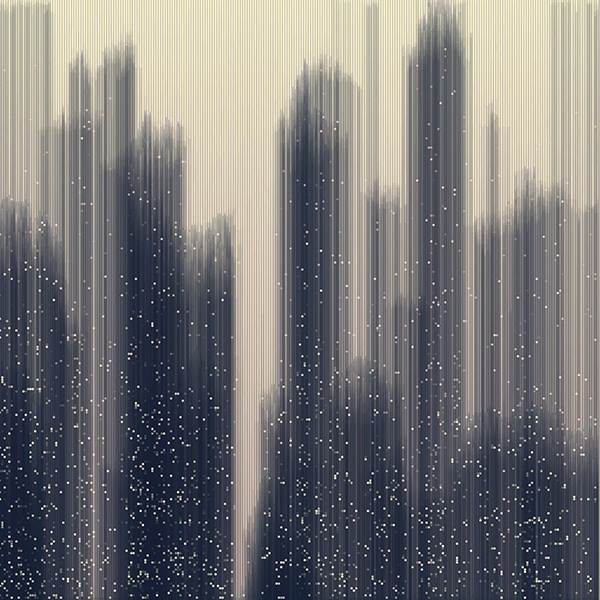

This week’s guest on The 21st Century Creative podcast is Tyler Hobbs, a artist who creates stunning images by writing a computer program to generate each new artwork.

It sounded like an interesting idea, but I didn’t have great expectations of the art itself. Then I landed on Tyler Hobbs’ website and I was entranced by what I saw.

There was definitely a futuristic, computerised look and feel to the images, but they also had an evocative, even haunting quality. The atmosphere of the artworks reminded me of some of my favourite ambient and techno music, or science fiction movies like Blade Runner and Metropolis.

I was also intrigued to see that quite a few of the images were marked ‘sold’ and unavailable. Instead of creating an image and printing it multiple times, Tyler is creating one-off original artworks. And when a collector buys the work, Tyler ships the image with a copy of the program used to create it.

The more I looked, the more absorbing the images became. I was also intrigued by Tyler’s writings about generative art and creativity. And questions kept popping into my mind:

How do you make this kind of image?

Why go to the trouble of writing a program instead of drawing or using photoshop to create the images you want?

How do you create such emotionally compelling images by writing computer code?

What can generative art tell us about the future of art?

In the end, I emailed Tyler and asked if he would come on the show, so I could ask him these questions and share the answers with you. He kindly agreed, and gave me a fascinating and insightful interview.

And not only did I learn a lot about Tyler’s artistic process, I also found plenty of things I could relate to in my own practice as a poet.

If you love futuristic art, or if you’re curious about the intersection of technology and human creativity, I’m sure you’ll find this conversation as riveting as I did.

And if you think computer art sounds a bit cold and cerebral, then I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised to hear what Tyler has to say about technology, emotions and creativity in the brave new world of generative art.

You’ll get a lot more out of this interview if you look at some of Tyler’s art as well as listening to him talk, so you can see some of his images here in the show notes and below in the interview transcript, and there are lots more at Tyler’s website TylerXHobbs.com

Tyler Hobbs interview transcript

MARK: Tyler, what exactly is generative art?

TYLER: Generative art can be a little bit tricky to explain sometimes. But kind of the core of generative art is that it’s pattern and process based. So in the current day, you’re typically going to be creating artwork through a program if you’re making generative artwork.

So for myself, my artwork is created entirely through programming. I don’t draw things by hand or use any sort of Photoshop or post-editing in any of my work. There’s a few exceptions to that. But largely, it’s done through custom computer programming. So I sit down and I develop a custom algorithm that will generate an image usually with no input. So it’s working from a blank slate. That’s the best description of how generative art is typically created these days.

MARK: So there’s no direct manipulation like with Photoshop or a mouse or a brush or a scanned images? You’re writing lines of code that then generate the image, is that right?

TYLER: Precisely. Yeah, a lot of people, whenever they see digital artwork, it’s hard for them to imagine not having interacted with it directly, but with generative artwork you really give up a certain amount of control because you’re working through a program.

And it’s also important to point out that typically, with generative artwork, you’re not working towards a single image, per se, you’re developing a program that has the characteristics to where, on average, the images that it outputs will look pretty good. So you’re specifying a whole set of aesthetic preferences and patterns in a system rather than developing one specific image.

MARK: So is this why on your website you’ve got a series of similar-looking images?

TYLER: Exactly. The programs that I create tend to involve a lot of randomness. And the randomness is used very carefully and very deliberately. I might use it anywhere from the high-level structure of the image in terms of how large forms and shapes are placed and organized, all the way down to very fine details, little random rough edges and splatters and things like that. I also use randomness for colors and color selection.

So every time that I run the program, I get a different output. And that allows me to do one kind of special thing, which is I can offer multiple images from the same program at a little bit of a lower cost to keep my artwork affordable.

MARK: Okay, so this is interesting. You run the program and then there’s a random element within that. So, when we use the phrase pre-programmed, we tend to think of it as something has been predefined. But for you, the program is actually a way of kind of scrambling that and giving up control?

TYLER: Absolutely, absolutely. I mentioned that the randomness was used very carefully. The randomness turns the program into a set of guidelines rather than an exact description of an image. So the randomness both helps me to give up control to some extent and allows things to happen maybe a bit more naturally. And it also helps for exploration. When you give up some of that control, the randomness will sometimes present new ideas that I wouldn’t have considered otherwise. So it’s definitely an ally in the process.

MARK: Okay, but we’re talking randomness rather than artificial intelligence? You wouldn’t say you’re creating an AI and using that?

TYLER: Yeah, definitely. AI is a very different sort of beast from what I’m doing. My programs are relatively simple compared to what AI does. AI is trying to build some sort of rough understanding of the problem that it’s working on, in some sense. And my program has none of that sort of memory or understanding that an AI has.

MARK: And what drew you to generative art rather than the more traditional kind?

TYLER: It was an interesting development. I’ve always really enjoyed drawing and painting and I did that for quite a few years. And studied traditional portrait drawing and figure drawing and landscapes for quite a few years. But I also went to university to study computer science. I had a very strong computer programming background and I was doing that as a day job at that point.

I had this awareness that artists are best served by trying to utilize things that are unique to them or that are part of their character or their life experience. And so you try and bring everything to the table that you can when you’re working on artwork.

And for me, it became pretty clear that I should try to involve the computer or programming in some way. And that did not immediately lead me to generative artwork. Some of my first attempts to link the two were laughably bad. But eventually, I got the idea that maybe I can write a program that would generate a painting. And that was the mindset that I had when I first started making generative artwork.

A couple of months after that, I started to stumble upon the generative art community and learn that it was already a thing. And I very quickly figured out that this was something that was going to work well for me and I’ve been pursuing it since then.

MARK: So you actually came up with the idea and then you realized that other people had developed it independently?

TYLER: Absolutely. And they were doing a much better job than I was doing at the time.

MARK: Tell us about the generative art scene. I’d never heard of it till I came across your work. How big is it? Who’s in it? What kind of range of work is in it?

TYLER: It’s an interesting scene. It’s not that large. And it never has been that large. Generative art has been around since the late sixties with some of the earliest computers, usually in kind of a military or scientific establishment. The first generative artists came out of that and so it’s never really caught on; the normal art scene hasn’t been a huge fan of it. And it’s just been a weird side project that some programmers have done in their spare time.

These days, it is picking up a bit more. And I think that’s primarily because of a couple of reasons. One is that the tools are much more accessible. So thanks to things like open-source software there are a lot better and more readily available tools for anybody to start playing around with creating generative artwork. And I think the other development is that as a consequence of that or as a consequence of more people having a programming experience, we start to get kind of more artists that also know how to program in the mix. And they’re starting to change what gets created these days. So generative art I do feel like is going through a nice uptick, but it’s still a very small community.

MARK: Okay. And people are coming at it from both sides. It’s the programmers who are thinking, ‘Hey, we could use this to make images.’ And then there’s artists who I guess whatever art form we have these days, more and more we’re using some kind of digital electronic technology to facilitate or record or publish that. So it’s converging from both sides.

TYLER: Absolutely, I would say it’s still usually dominated by programmers deciding to play around with doing something a little bit more fun with programming then their normal day job allows them to do.

But there have always been artists that have stumbled into this arena as well. So one of the most well-known generative artists is a guy by the name of Manfred Mohr, and he was one of the early pioneers and he was an artist that kind of entered the space and he had a very different approach from the programmers. And so, it brings a totally different mindset, which I think is an awesome and very positive thing. So, yeah, people are kind of attacking it from both ends.

MARK: And do you need to be able to code? I mean, if I’m a painter listening to this thinking, ‘Wow, I’d like to get into that but I don’t know how to write code,’ is that going to be a big barrier to entry for me?

TYLER: I would say that coding makes a very big difference. There are ways to do it without coding. There are some environments that are really a type of programming but maybe in a more visual style, rather than textual controls. You have kind of visual controls. So that’s one option for people who don’t know how to program. Another is that, and maybe we’ll talk about this a little bit later, but some elements of generative artwork don’t strictly require programming and you could manually produce some similar results.

But I’ve got to tell you, the programming is such a powerful tool that it makes a huge difference if you do know how to program, even if you just know how to program a little bit. It’s honestly not super complicated programming. You don’t have to be a mathematician or have a computer science degree in order to do it. It’s relatively simple. But when you’re working through programming, there’s a much more natural dialogue between yourself and the computer. You’re kind of speaking in the computer’s terms. And something about working in that way I think helps to explore the possibilities of generative art more fully and more naturally.

MARK: So do you enjoy writing code like in the way a novelist, for instance, might enjoy writing prose?

TYLER: I would say it’s pretty similar. I’d say probably novelists have parts of their book that just flow out easily. And then they have other parts where they get stuck and have to think about exactly what to write very carefully for a week straight. I have those same sorts of experience with code. Most of the time, it comes out pretty naturally. I’ve been writing code for a long time and so it’s a pretty natural way for me to already be thinking about the problem.

But yeah, every once in a while there are the thorny problems as well. It’s tough to think about how to write the code correctly. Sometimes it’s hard to translate a visual idea into a program to think about how you might build that up from patterns and processes. But yeah, the actual natural act of writing code feels good to me. I definitely get in the zone when I’m working on these programs.

MARK: Do you think there could be an analogy with music? I’m not a musician so it’s always pretty amazing to me to watch a trained musician just pick up a piece of equipment. And the technical ability that they’ve got and the muscle memory and so on… to them it’s invisible because it’s so finely honed that they’re just focused on their emotional expression through the instrument.

TYLER: Yeah, absolutely. There are a lot of similarities between the two and I would say it’s most similar actually to composing rather than playing an instrument.

MARK: Okay, yeah.

TYLER: There’s a level of freedom that you’re giving up where the final product maybe won’t be exactly what you have in mind. So, you know, the composer probably hears their score in a certain way in their head. And then whenever the orchestra actually plays it, you know, things might end up sounding quite a bit different. So that there’s that sort of difference.

The other is that at least I’m imagining… I do play some music, but I’m definitely not a real composer. I have to imagine that they kind of hear everything working together at once in their head sometimes. And then they have to carefully think about how to break that down into individual parts and patterns and components that will add up to what they’re looking for. And there’s a lot of similarity in that to how I think about building up a visual image through different elements of a program.

MARK: Coming back to the analogy with the score and the composer, it strikes me maybe you could think of the score as being software code for the orchestra?

TYLER: Absolutely. Yeah, that’s exactly what it is. There’s a certain amount of flexibility in that score that’s open for interpretation. And some composers, especially in the maybe postmodern era of music, have intentionally left a lot of ambiguity in the score. And I do exactly the same thing in my program, but the ambiguity is there very intentionally.

MARK: Staying with the idea of intention and randomness and unpredictability, do you start off with an image in your mind that you think, ‘Okay, I’m going to write a piece of code to produce that,’ or is it more open ended, like you write a piece of code and see what comes out?

TYLER: Yeah, I would say it’s much more like the latter. I certainly never have a finished image in mind whenever I’m first beginning a program. At best I have a technique that I know I want to experiment with or maybe I just wrote another program that turned out pretty well and I have an idea for how I can change that. But for me, it’s a very exploratory process, and the medium really lends itself to that well. So I can start out by writing a very simple program. I can run it very quickly, see what the output looks like. And if I liked it or don’t like it, I can go back and change the program and run it again, accordingly. So the output is very mutable.

It’s really easy for me to experiment with new things. And if I don’t like it, I can roll back the changes pretty easily. And that’s not something that every medium has. So I really try to take advantage of that by working in a very exploratory and an open-minded way. However, I will say, as far as individual changes to the program go, say I want to make a certain visual change to the program. I usually have a pretty good idea about what needs to happen in the code to correspond to that type of visual change.

So at this point, I’ve definitely developed a sense of, ‘If I change the program a certain way, this is what it will likely look like.’ But it’s also easy to escape that realm and for me to change the code in a way that I have no idea what’s going to come out. And I’ll try that just to see if it happens to be amazing.

MARK: So when the image comes out, it’s a surprise to you?

TYLER: Yes, it’s a surprise to a certain extent. Sometimes it’s a really big surprise, sometimes it’s along the lines of what I expect, but I never could have predicted all the details that are in there.

MARK: What’s that moment like when you first see it? Does it flash up on the screen or does it come out of the printer or…?

TYLER: It flashes up on the screen. And that moment can be very exciting. There have definitely been a lot of moments where I make a change not knowing what the output is going to be. And I see the results and suddenly I know where this piece is going. Like it’s the ‘aha’ moment. It clicks when I see that image. And since a lot of my work kind of begins by stumbling around in the dark, there’s usually that kind of one critical change that really puts the…I see it and then I know what the structure of the work needs to be like. I love that kind of surprise element of creating the work.

MARK: And I think probably somebody listening into this, whatever their art form is, can almost certainly relate to that. And because when you think about creating artwork from computer code, I think the initial response that a lot of artists might have is ‘Well isn’t that a bit cold? Isn’t it a bit cerebral? Isn’t it a bit programmatic in the bad sense?’ But what you’re describing is very familiar to me as a poet. Sometimes you change something and, ‘Oh,’ or a line comes in or a rhyme pops out.

And the whole thing looks different, and there’s that. I had the poet Mimi Khalvati last season talking about poetry as discovery. She said, if you know what you’re going to write, then it won’t be a poem. But you go in and you surprise yourself.

And what you’re describing, I think it’s that kind of ‘aha’ moment that’s probably familiar to creators in all kinds of different fields.

TYLER: I think you’re absolutely right. I think if you’re not going into the work with an open mind about what it can be, then you’re really limiting yourself in terms of you’re not trusting your intuitive response, right? The preplanning of a work is a lot more cerebral. And when you’re actually in the middle of that work, allowing yourself to respond to it and change it as it develops based on how your soul or your spirit reacts to the work. That’s going to give you a lot better result, I think. And, yeah, I try to do generative art the same way.

Like you say, it sounds like a very cold logical form of artwork. And I can certainly see how people see it that way and how creators can kind of fall into that trap when they’re getting started with it. You have to learn to not have such a firm grasp on everything and allow yourself to explore and allow yourself to react to things and just take directions based on your gut reaction.

MARK: Right. And this was my initial response when I first saw your work was just, ‘Wow!’ It’s so beautiful and it’s so evocative. And there’s some really haunting imagery in there.

I read an article on your site where you talk about the importance of evoking an emotional response in generative art. I’ll link to it in the show notes. You’re quite critical of the generative art scene because you say a lot of it is too cerebral, too intellectual.

Can you say a bit more about how on earth do you get that level of emotion into something that’s computer-generated and programmed in this way?

TYLER: I think just to expand on what you were saying, it’s given that a lot of the people creating this form of artwork do have an engineering background, a math background, maybe a computer science background, we’re very used to and trained to think in a series of logical, clearly defined steps. And as artists know, that’s not something that really tends to work well for artwork. Art has to be guided by your feelings, your internal response to the artwork.

And so in that article, I’m trying to push generative artists to listen more to that internal voice. And in my own work, that’s something that I try very hard to do. I try to base my judgment and decisions around the work entirely on what my internal reaction is. So if it evokes some sort of an interesting emotional response in me, that’s something I want to try and follow. And if the work doesn’t do that, for me, if it’s just a technical display or something like that, then I know that it’s kind of failed at becoming a meaningful piece of artwork.

And it’s really easy with something like generative artwork to get wrapped up in the technical aspect of it to kind of show off your technical chops. And a lot of forms of artwork in that way, certainly, I know for drawing and painting, it’s easy to get pulled into that trap as well. But I think it’s always worth it to take that challenge of moving to the next level beyond just technical abilities, and really try to focus on the emotional response and in particular, your own emotional response to the work. At least that’s my strategy.

MARK: The poet Robert Frost once said, ‘No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader,’ which is to say, if you’re not moved by the writing as you write it yourself, then how on earth is your reader going to be moved?

So for you, it’s got to have that emotional reaction for you when you first see that image. Otherwise, it’s just not interesting to you.

TYLER: Yeah, absolutely. I think the only emotional reaction that you can really gauge honestly and accurately is your own as well. So even your best friends might say, ‘I love the work.’ But you don’t really know for sure if it resonates for them and, if it does resonate, exactly how it resonates for them. And so just out of a pure practicality as well, you have to use your own emotional reaction as a guide because it’s the only thing that you get really clear signal from.

MARK: Okay, Tyler, you’ve given us a really fascinating insight into the process. Let’s talk a bit about the end result.

What is it that you produce as the artefact? Are these like a series of prints? Or is it a one-off artwork in its own right?

TYLER: I typically execute the work through prints, but I prefer to do single-edition prints. So I never print the same image more than one time. I talked earlier about how randomness allows me to generate multiple different images from the same program. So sometimes as an in between I’ll take one program and generate four different images from it. And so I can sell those for a lower price than if I could only sell one image from the program. I also really like to try to work through non print mediums as well. So something that’s a lot of fun to work with is a pen plotter. So for your listeners who may not be aware…

MARK: And for me!

TYLER: And for you, a pen plotter, it’s a really simple robot. It’s a two-axis drawing robot. And so you stick a pin in it, you give it instructions for lines to draw, and it carries out the whole drawing for you. And of course, this has very different properties from working with a print. You can’t paint over things when you’re talking about a plotter. And you have to be careful about parts of the drawing not going off of the image. But that gives you kind of a real-world grittiness that you don’t get in a print. There’s something cool about that.

Lately, I’ve been experimenting with doing something similar except putting a paintbrush into the plotter instead and having it periodically dip that brush to paint. So plotter paintings is another thing that I’ve been working on. And, of course, I have the option of displaying artwork with digital displays or a projector, but typically I prefer the experience in the appearance of a print over a digitally-projected image.

MARK: So most of the time the end result is what looks like a print that you would hang on the wall in your home.

TYLER: Exactly.

MARK: And did I see somewhere that you include the code when you sell the artwork?

TYLER: That’s correct. I don’t typically publish my code. But I do feel like it’s an important component of the artwork, whenever somebody takes the time to appreciate my artwork and purchases a piece. I feel like they deserve to know and maybe understand a little bit about the process that went into creating that image especially because the image is just one potential output of billions from this program. So it’s a small snapshot of the program. And so, yeah I consider the program to be an important part of the artwork and so I include a copy of that along with the artwork with any sales.

MARK: That’s something Turner never offered, right?

TYLER: No!

MARK: So we talked a lot about technology and it’s all quite futuristic. What about artists from the past? Are there any artists that you would say have been a big influence on you? Or do you see yourself as the latest iteration of any kind of tradition from the past?

TYLER: There are definitely older traditional influences on me. I really enjoy a lot of abstract expressionist and colorful paintings. That’s what I tend to emotionally react to. And so I feel like I try to capture some of the spirit of that in my work but there definitely is a lineage of generative art at this point. And I would say there’s a few early kind of progenitors of that.

Dada in some ways you could say played a role in it because Dada started to integrate the use of randomness. John Cage used randomness when composing some of his scores. And later on an artist by the name Sol LeWitt started to create work that was simply a set of instructions. So, three or four very simple instructions for how to execute a drawing on a wall.

And this is a form of early generative artwork that’s not executed by a computer, it was executed by human instead. But the idea is the same. It’s a simple process or pattern that if you follow it results in the creation of an interesting piece of artwork. So I feel like I fall in that same lineage and if I’m successful with my work, I hope to have expanded the emotional range of generative art work a little bit.

MARK: And where do you see this going? What’s your sense of what the future of generative art might be or the future of art and technology?

TYLER: Well, I could speculate for a really long time on that front but there’s a lot of really interesting things in the pipeline. And, of course, new technology always has a big impact on artwork. And that’s definitely the case with generative artwork as well. So a couple of the new technologies that I think will produce some very interesting artwork, one is VR, virtual reality. And I think what could be really cool to see would be generative 3D sculpture in a VR environment.

The key distinction between sculpture in the real world and sculpture in VR is that you don’t have physical limitations anymore. You don’t have to think about the weight of things or the scale of things. Generative artwork doesn’t have to be in 2D, it can be in 3D as well. And I think it would be really interesting to see people explore that space of generating large-scale 3D sculptures that you can walk around and interact with in virtual reality. I have no doubt that that will be a thing soon enough. And if I was a 3D sort of person, that’s what I would be doing.

Another technology that’s going to have a really big impact and is already producing some interesting results is something called deep learning. And this is kind of one piece of what you might call AI. It’s one particular technique for teaching a program to learn something deep and structural about images in a way that it can also generate images based on what it seen in the past. So you may have seen or some of your listeners may have seen Google released something called the DeepDream software. And you can make it hallucinate these images that are filled with eyes and dogs faces and they’re very, very colorful and… I don’t know if you’ve seen this in particular.

MARK: I haven’t but I’ll make sure I link to it in the show notes.

TYLER: It was it was very popular when it came out and I’m sure some of your listeners will know what I’m referring to. So that’s one of the first steps in that. But really the key development is that programs are starting to understand images in a more structural way. So they don’t quite know this but they have a sense of, ‘This is an eye. This is what eyes look like. This is the range of what an eye might potentially look like.’

And so if you asked it to generate an image of an eye or generate an image of a face, it’ll get all the components mostly there in mostly the right place. So it’s starting to produce some really interesting artefacts. And right now, it’s more kind of in the tool-building stage right now. But I have no doubt that some really good artists will get their hands on that and produce some really interesting work in the next five years.

MARK: And just to take that idea for a walk, if we were to extrapolate from that AI producing artwork independently, so just the AI was generating it and there were no human interactions, do you think that could conceivably be as moving as a piece created by a human?

Circling back to what we were saying about your own artwork, that emotional appeal of it, it sounds like it comes from the fact that when you see it, it moves you first of all and then you will select and put that out there.

Do you think humans could find AI-generated art as moving as that? Or would it inevitably lose something?

TYLER: That’s an incredibly deep question, Mark. It’s going to be a tough one. But I have some thoughts on this. So I think an important limitation of AI as it is right now is that it can only see and remember what somebody has trained it with. AI is very much influenced right now by what data set it’s been fed in initially. And so in that way, the person who’s developing or controlling the AI has a very large impact on what it produces. So AI is very far from being independent right now.

Let’s imagine a future where an AI lives in a robot and it can go around and collect its own physical images and sensory input and it’s working based on that. I think it’s going to be really tough for an AI to produce artwork if we define artwork as being… it’s always hard to define artwork. But if we define artwork as being about the human experience in some way, then just from that definition, I don’t think an AI is going to be able to create truly new artwork just because it doesn’t experience and won’t experience the world and life in the same way that a human does.

But maybe the AI can very successfully create artwork that is meaningful to itself or to other similar AI. And in that case, it might be a very successful artist. But yeah, it’s going to be really interesting if this stuff develops to see what an AI’s idea of artwork is once they can move beyond kind of the mimicry as the main operation. I have no idea what that’s going to look like or how successful it might be. But I think it’ll give us some interesting insight into ourselves and how AI might fundamentally be different from humans.

MARK: Okay, let’s leave that thought hanging out there in the future, and we’ll come to it with the progress of technology someday.

Let’s come right back to the present and today and to what our listener can do based on the ideas that you’ve been putting across in today’s interview. It’s time for the Creative Challenge.

This in one was maybe more challenging than some given that, clearly we’re not going to go and ask you to start learning computer code and writing it this week. But I think Tyler has come up with quite an elegant solution to how we can all get a little bit of taste of generative art.

So what’s your challenge, Tyler?

TYLER: My challenge is, like Mark said, I don’t think it’s reasonable to expect people to learn programming just for a challenge like this. But you can really get the spirit of generative artwork by working through patterns and processes and potentially involving randomness. So my challenge would be for your listeners to try to create a simple small set of instructions that if you follow them will result in a piece of artwork being created.

So this is sort of like what Sol LeWitt’s work was and maybe I’ll give you a couple of examples. If I was going to write some instructions to produce a drawing, I might say something like, ‘Step 1, draw a triangle. Step 2, split the triangle in half by adding a new line. Step 3, repeat from step 1 for each of the new triangles you produce until the lines get so small you can’t fit any more in.’ And so there I’ve created a program in some sense. There’s only three instructions, but it loops back on itself. And I can continue doing it until I’ve produced an interesting result.

And you’ll notice that the instructions are kind of ambiguous. The person executing it has quite a bit of leeway as to what type of triangle they draw, how they split it in half exactly. And so there’s a lot of interesting variation that might come out of the results as well. So to give you kind of a different example, you might be able to produce a poem with a certain set of instructions. And I’m not a poet, so tell me how good or bad this idea might sound but…

MARK: I’m all ears!

TYLER: If we can introduce some randomness here, I’ve seen some very simple rules in poems. Maybe you’ve seen the same ones where each successive line has one fewer character or syllable than the line above it. So that might be a very simple rule that you can repeat as you work on the poem.

You might also be able to include an instruction with some randomness like each line has to begin with a randomly selected adjective for example. Or maybe you can come up with a rule about something about the grammatical structure of each line or the rhythm of each line. I’m not a poet so it’s hard for me to think in that line.

MARK: There’s a whole catalog of verse forms. As you were describing it, I’m thinking, ‘I guess the Petrarchan sonnet is a kind of generative art, because it’s got to have 14 lines and there’s the first 8 lines have to put together proposition and then the last 6 have to answer it. And that the rhyme has to go in a certain pattern and whatever.’ So maybe I’ve been doing generative art all along!

TYLER: Exactly! There’s a lot more in common with other parts of artwork than you might think.

MARK: And it also reminds me of my friend Mick Delap when we were working on Magma Poetry magazine together. He published some poems based on the Fibonacci sequence where the number of syllables in each line had to…was in the… I don’t know what sequence…

TYLER: The Fibonacci sequence.

MARK: Yeah, but you take the numbers of that and then it’s the number of syllables in each line. So it gets longer and longer as it goes on and there’s a certain quite an interesting results. So yeah, I guess maybe we are more generative than we realize.

TYLER: Yeah. And I think you’ll hear a lot of artists say that constraints yield creativity. Generative art is kind of a way of thinking very carefully about those constraints. My hope is that your listeners will self-impose some interesting constraints and maybe come out with some new results.

MARK: Well, this is great, Tyler. So just to sum up, the challenge as I understand it, is to write a simple set of instructions or rules to produce a piece of art and it could be in any medium.

TYLER: Exactly.

MARK: And is it something that you execute yourself? Or could you give the instruction to someone else? Or could it be either?

TYLER: It’d be really interesting if you gave those instructions to somebody else. I think that if you’re writing instructions for yourself, you maybe have a certain idea about how to execute them. And it’d be really interesting to see how somebody else interpreted those and how it differed from your expectations and that would let you know if your instructions were actually really good or not. So I would highly encourage having somebody else execute it if you can find somebody that will do that for you.

MARK: So, listen, if anybody does this and you want to share the results then maybe you could paste them or a link in the comments to the show notes because we’d be really interested to see what you come up with. So if you go to 21stcenturycreative.fm/tyler and leave a comment there, we would really love to see what you come up with. I think that would be very interesting.

TYLER: Yeah, that’d be fascinating.

MARK: Tyler, thank you. This has been absolutely fascinating for me and I’m sure for our listeners as well. Where can we go to find more about you and your work online? Is it tylerhobbs.com is your website? Is that right?

TYLER: It’s Tyler L Hobbs, http://tylerxhobbs.com just the letter L there in the middle, T-Y-L-E-R X H-O-B-B-S. So if you just…or if you just Google “Tyler Hobbs,” you’ll find my website as well. That has a link to my Instagram, which is where I tend to post a lot of images. But if you’re interested in some of my writings about generative artwork, I have those on my website as well.

MARK: It’s really worth it. It’s mesmerizing to go and browse through Tyler’s site and then read the articles and people can buy prints direct from the site as well, can’t they?

TYLER: That’s correct.

MARK: Right. And the Instagram as well I heartily recommend to see the latest stuff that Tyler is doing. So, Tyler, thank you so much. This has been an absolutely fascinating journey and we really appreciate you taking the time for this.

TYLER: Mark, thank you. I’m glad that more people are starting to hear about some of the ideas behind generative artwork and find it exciting. So I really appreciate you having me on and letting me talk about my favorite subject for a while.

MARK: Great. It’s been a pleasure.

TYLER: Likewise.

About The 21st Century Creative podcast

At the end of the interview, I ask my guest to set you a Creative Challenge that will help you put the ideas from the interview in to practice in your own work.

And in the first part of the show, I share insights and practical guidance based on my 21+ years experience of coaching creatives like you.

Make sure you receive every episode of The 21st Century Creative by subscribing to the show in iTunes.