Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Today we kick off Season 5 of The 21st Century Creative, the podcast that helps you thrive as a creative professional amid the demands, distractions and opportunities of the 21st Century.

Our first guest is John T. Unger, an artist who makes art on a big scale, and who takes full advantage of the opportunities of 21st century to both make and market his work.

In the first part of today’s show I talk about the changes we have all experienced since Season 4, with the advent of Covid.

Although most of the interviews for Season 5 were recorded before the pandemic, I have rewritten the rest of the season extensively, to share my thinking on how we as creatives can respond to the disruption with creativity and resilience.

I also introduce The 21st Century Creative Membership Group, on Patreon, which I am starting this season to help you stay creative, productive and motivated in spite of everything.

Exclusive Member content will include Goal-setting and Accountability Videos, Members’ Q&A Sessions and other insights and tips not featured on the podcast.

In the light of the pandemic situation, Membership is currently on a pay-what-you-want basis.

As well as giving you access to the exclusive Members’ content, your Membership fee will also support the podcast and help to make it sustainable.

John T. Unger

From performing his poetry on stage at Lollapalooza in 1996, to bartering a mosaic to a bank as a down payment for a house and studio, to displaying an American flag created from over 20,000 Budweiser bottle caps at the 2015 Stagecoach Music Festival, John’s art practice has been as much about making good stories as making good art.

His work has been featured in The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, Smithsonian Magazine and many other magazines, newspapers, books and TV shows.

He is best known for his sculptural firebowls, which he makes from scrap industrial steel, cutting by hand with a plasma torch at 45,000° Farenheit – which he says is 4.5 times as hot as the surface of the Sun or the Earth’s core.

Since 2005 he has sold more than 2,000 firebowls, shipping to all 50 US states and over 20 countries. Firebowl clients include Calvin Klein and many restaurants, hotels, churches and public spaces.

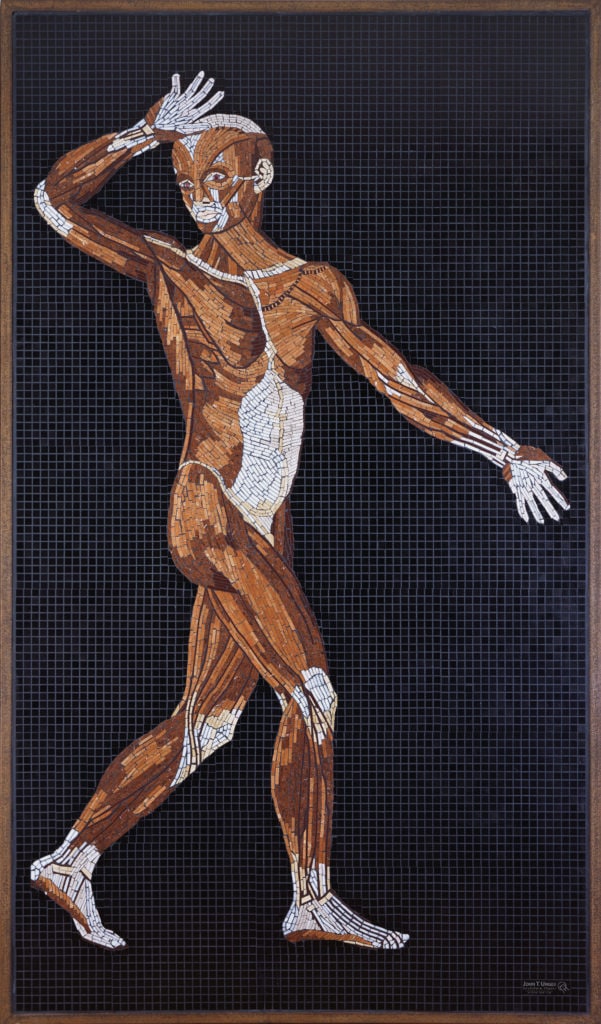

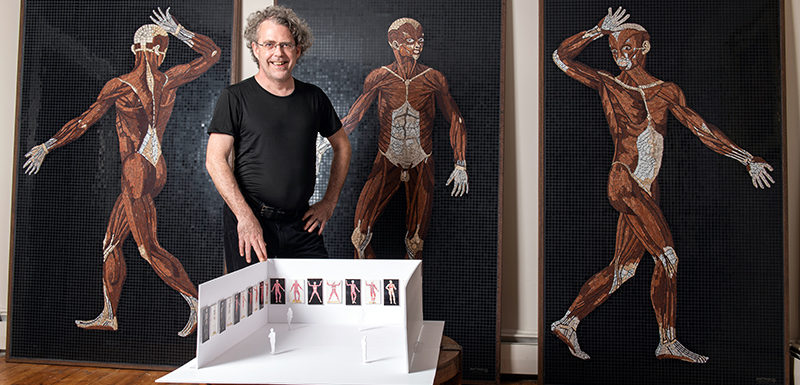

His current project, Anatomy Set In Stone, is his biggest and most ambitious yet.

Using marble, stone and precious gems he’s creating a series of 14 life-size mosaics that replicate a series of anatomical engravings by the 16th Century artist Bartolomeo Eustachi.

Each mosaic is seven feet high by four feet wide and presents the figures at life size— so that viewers can stand before them and see anatomy as though looking in a mirror.

The project requires John to cut over 3 miles of stone by hand, spending several years and tens of thousands of dollars to fashion it into 392 square feet of detailed mosaic.

When he finishes, John’s ambition is to turn the engravings into a touring exhibition for museums and galleries around the world.

Like most of the interviews this season, this one was recorded before Coronavirus took the world by storm, so we obviously don’t talk about it. But I think this is a great interview to kick off the new season as John’s energy and resilience are the kind of qualities we all need to display right now.

So if you’re curious about what happens when you approach your work and career in an boldly unorthodox manner, strap yourself in for this conversation with John T Unger.

You can learn more about John’s work at his website, and watch videos of him at work via his Facebook Page and YouTube channel.

John T. Unger interview transcript

MARK: John, at what stage did you start to think of yourself as an artist?

JOHN: Kind of always. I’ve made things since I was a wee little kid. I got my first jackknife when I was four and started making things with the second one because the bullies across the street stole the first one, actually, the MacNelly brothers.

MARK: But they didn’t stop you!

JOHN: No. Nobody can. Nobody has. Anyway, I’ve always made things. And initially, my big love was reading, but I’ve always loved making things too. I thought I wanted to be a poet for a living and I spent about 15 years trying to do that even winning poetry performing live on stage at Lollapalooza. I was invited to tour with the show, but it was at your own expense. If you weren’t getting paid, you couldn’t work while you’re doing it.

And that was the thing with poetry is literally, I would have people come up to me at readings and say, ‘Oh, that poem changed my life’. And I’d be like, ‘Hey, I’ve got a book of them here for $6.” And they’d be like ‘Nah.’ And I’m like, ‘Okay, I obviously didn’t change your life enough, buddy. Not so much as a hamburger’s worth.’ But, I spent a lot of my late teens and 20s trying to find ways not to have a job so I could focus on poetry and reading and writing all day, every day. And there was always a side hustle.

MARK: That’s a familiar scenario to me, yeah.

JOHN: Right. And so at one point in time, I was making jewelry, and hats, in Seattle and selling them on the street so I could be a poet, or I was playing music in the street busking, playing harmonica, so I could be a poet. And then eventually, I wanted to make books and I’d given up on the idea of a publisher doing it. And so I was going to self-publish, and I learned graphic design. And then I did that for a living while I wrote poems. And then I started doing artwork, partly because I really wanted to own artwork and I couldn’t afford the stuff I liked. Mostly, I liked African and Asian work that’s pretty affordable as art goes, but not if you’re a poet.

So I made my own and eventually, I realized people will pay for artwork. And when we had the first big crash of the internet around 2000, or whatever, all of the design work dried up, and I’m like I’m not going to invest in learning to do something else for dollars. What I’m going to do is I’m just going to go full-time into making art. I’m going to do that. I’m going to pay my bills with it. I’m not going to work.

And I realized if I took the 8 to 10 hours depending on commute, that had been for a day job and spend that time learning how to sell and market my artwork and doing that, then I could spend all night making the artwork the same as I’d been doing while I had paying work. It was really sketchy. I had to couch surf for a couple of years but I made it work.

I had a lot of friends at that time who had gone to art school. I started really doing the art in Chicago, and it was a great place. I was in a neighborhood called Pilsen, which was where all the artists moved when the Wicker Park gentrified. Sort of like, probably 500 working artists, some of them were making a living, most of them weren’t. But it was a great community for me to learn how to not just do the artwork, but how to get into shows and court galleries and all of the business and social parts of it that I wouldn’t have known because I was self-taught.

MARK: So right from the beginning, you made a conscious decision to address both sides of this, the making of art, but also the business and social aspects of it?

JOHN: Yeah, and I’m better at some parts of that than others, which is probably true for everybody. It’s funny, because a lot of the time in an arts community, or at least in the one where I was in Chicago the art buying public was… people were at odds with it. It was like, people felt like ‘Oh, it’s people who come down to our dicey neighborhood, from the suburbs, and we have nothing in common, but sometimes they buy art.’

At first, you roll with that, then you go, ‘Well wait a minute. A) they’re making a trip to your part of town, which you’re not doing for them. And B) they wouldn’t be here if they weren’t interested in the art. And if they’re interested in it, especially enough to give you money, then odds are you do have other things in common.’ And over the years that’s proved very true.

With some of the customers, I have just click a button on the internet and they buy a thing, I ship it to them, there’s no communication. There doesn’t have to be. But the people I have interacted with, for the most part, have been really cool people. And some of them have actually become friends. Some of them I’m just like, ‘Well, thank you for making this possible.’

MARK: They obviously have really good taste, right?

JOHN: I like to think so, right. It was that early period where I left Chicago because I lost the paying work I had and everything fell apart. I lost my place and the end of my thumb, and my girlfriend, and all of the things. I went back to where I grew up because there was some free rent there, but there really was no culture. It’s the top of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. It’s six hours north of Detroit. Yes, there are artists, but because it’s a very conservative place, it’s mostly going to be landscaping and some things, which is fine, but not my thing.

I got stuck there for about 10 years. I had a fortuitous event where I was leasing a former convenience store and house with an option to buy. That was really not very realistic because it was early days, I was just barely scraping by. And winter came and the studio building started making a scary noise and I went up on the roof to get the snow off and the building fell right out from under me! It just collapsed and I jumped off! I was fine. I have reflexes. I have to. But…

MARK: Where did you land?

JOHN: In a lot of snow so it broke the fall nicely. The snow was, I don’t know, 6 feet tall or something. It was ridiculous. I had purchased the two acres that got more snow than anyplace else for hundreds of miles, I think, lake effect snow in a valley.

But anyway, the bank came out to look at the damage and they saw the artwork I was making. And it was a house that they had repossessed or whatever the real estate word is. And they didn’t want the house and I still kind of did. They proposed that I do a big mosaic sign for their main branch office as the down payment. And that’s what made it viable. And so I finally had a house and studio that I could work out of. The house payment was $300 a month. It was nothing. So that was a really good launching pad.

MARK: Wow so, that’s how you got on the property ladder?

JOHN: Yeah, the collapse of the building knocked out the natural gas, so there was no heat or water because the pump froze for the entire winter. I just had like a kerosene heater that wasn’t meant for indoors. I probably lost some brain cells to monoxide. But that was when a friend of mine suggested I should start a blog. This was back in the day when there were probably about 500 blogs on the planet. It was a pretty new thing. At first, I thought he was nuts but I mean, I had time on my hands and I was freezing. So I converted my website to a blog and you know, really went at it.

I was looking up before our conversation, the first piece of art I sold online was a little luminary on June 4th, 2005, which was exactly two weeks before Etsy even launched. This was still when it was really uncool to be commercial on the internet.

MARK: Oh, yeah, we had Brian Clark talking about that last season and the amount of vitriol that he got in some quarters for daring to suggest that a blog might be useful for selling things…

JOHN: Yeah. It was also when everything was still a very fresh startup if it existed at all, and you could actually… At that point in time, social media didn’t even exist yet. But in the early days, they were very consumer-focused. They wanted to make a big platform people wanted so they were responsive to users in a way that they’re not anymore. And you could call the GM of Typepad or I talked to a lot of people in the development departments of a lot of the early social media companies and web hosting companies and was like, ‘I have this idea for a blog that is also a store.’

And it’s really funny, nobody wanted to do that. And it wasn’t until years later, I guess I was apparently the tenth person to sign up through Shopify, and Shopify was a store that had a blog. But in a way, that’s not quite the same thing. And the problem then with the Shopify is it’s built on Ruby on Rails, and so you really need to learn a whole new kind of coding to change it. And I really struggled with that.

And it’s important to say too, I was pretty motivated to make decent money in the beginning because A) I hadn’t had any, B) I had bought a house but a house that had fallen down. And the rest of the house seemed like it might do that any minute. And I really needed to get out of there into a better place. So I needed to save up for a down payment on a real house.

Then we looked at a bunch of different places, and eventually, we wound up here in Hudson, New York, again, thanks to somebody I met through blogging, Mary Anne Davis, who’s a potter, who I met on the internet first when she was blogging in the early days, and then at South by Southwest and met her in person. And then she was like, ‘Oh, you should look at Upstate New York. You should look at Hudson.’ I had always just assumed that everything north of the city was million-dollar homes for weekends for people who lived in the city.

But honestly, a lot of Upstate New York is former mill towns that are rather affordable or were. So we wound up here. It would have been nice to get here 10 years earlier, but we have a beautiful 150-year-old farmhouse on top of a little mountain with a view of the mountain. It’s really on a big 3,000 square foot barn that’s probably about 150 years old. It’s a metal shop and a little barn for storage. And sadly, the mosaics I’m doing and the steelwork that I do can’t happen in the same place. You can’t have marble dust on your welds and you can’t have rust on your stone.

So I’ve commandeered half of the ground floor of our house for the mosaic studio. And fortunately, I married somebody who knew what she was getting into with an artist and who’s very supportive. We didn’t really use the living room and dining room anyway. We don’t do that much entertaining.

MARK: So you’ve got this setup where your work and your life are really intertwined. We’re recording this interview a little later than most interviews. As I gather, you work pretty late.

Maybe you could talk us through your working day, and maybe it goes into the night as well.

JOHN: Oh, it does. Left to my own devices, I would be awake 20 hours and sleep 10. That’s what my biology wants to do. And you could do that as a poet who didn’t have a job or anything. I did, but if you want to have a marriage and a business, you really can’t have your day shifting forward six hours every day. It just makes it impossible to plan anything. So I’ve adapted and it works better for me to be awake at night. So I got up around noon, have coffee for a couple of hours, do anything that requires 9:00 to 5:00, scheduling in the remaining couple hours of the day.

And then Marcie and I sit down together to dinner pretty much every day. In the early days, the art always came first and that’s why all of my ex-girlfriends are ex-girlfriends. If you did an entry poll and an exit poll of those relationships, ‘Why did you date him? Why did you leave him?’ The answers would be exactly the same. ‘He’s so creative. Oh, he’s so dedicated to his art.’ And when Marcie came along, I was like, I’ve got to do this different. And so it was a very big shift from how I’ve operated the rest of my life. I’m like, okay, from dinner until she goes to bed is time that we spend together and that’s just sacrosanct.

And she’s the opposite, we pass each other in the morning a lot. She gets up at like 5:00 or 6:00 in the morning most of the time. So what works really well is actually we have a really good block of time that we spend together and we see each other throughout the day or we used to when she was unemployed. She’s a nurse now so now she’s got jobs, or she’s got work. But we get time to be to ourselves, which we both appreciate and we get time together and it works really well. But anyway, then she goes to bed and then I’ll noodle around for an hour or two and then get going on the mosaic and usually work until like 3:00 in the morning. And spend a couple of hours winding down with some whiskey and streaming media and go to bed.

MARK: It sounds like a perfect routine.

JOHN: It works out. If I were more ambitious, I would do things differently, and I did, and that’s the thing. When I was in my 20s and I had nothing and I really wanted to have something, I would go to the day job for 10 hours, including commute and I would work another 10 hours at night in the studio, and I would sleep 4 hours and do it again. There’s a lot I don’t even remember from that period of my life because if you get no sleep, your brain doesn’t do a lot of long term memory. It’s all a bit of a blur.

MARK: Okay, so you touched on the mosaics which I want to come back to, but before we get there, the thing that you’re best known for over the years has been the Great Bowls O’ Fire.

Can you tell us a bit about what they are, where the inspiration came from, and how that side of your work works?

JOHN: Sure. I’ve been doing them for about 14 years now. And the inspiration was when I started out, I was using recycled materials almost exclusively for all my art. And part of that was an ecological idea. Part of it was that it was more affordable when I was starting out. Part of it was that I just have this deep abiding love of objects and materials and historical things.

I spend a lot of time looking at objects and materials and thinking about them. A lot of my early work was turning one thing into another. And that was sort of this alchemy. I made masks out of shovel blades because they’re shaped like a face, that was cool, and so on.

So I was in the scrap yard shopping for materials and saw them cutting up this propane tank and the end cap of it fell off and became this large bowl and I was like, ‘Oh my God!’. Because making a giant bowl like that isn’t something you can do in any art studios. There’s like about six factories in the US that stamp these things out with a big stamp the size of a house and they’re around seven or you know, maybe there are… but there aren’t very many.

And so I saw this thing and immediately I had the idea for the Great Bowl O’ Fire, of cutting flame shapes around the edge of it to make it into a bowl that you would have fire in, a fire pit. And at that point in time, nobody had ever done anything like this with that. Obviously, there were fire pits, but there weren’t very many artistic ones. They’re mostly mass-produced, or they were masonry and custom-built. So I had this idea and I loved it because it’s like, okay, I’m taking this container for flammable gas, and using a torch to cut flame shapes in it so that you can have a fire in it, that you could even plumb for gas if you want. It was just like fire all the way down.

And that’s a big part of how I think about the work I make. Because I started as a poet, and because that was so much about metaphor, and because the art that I studied most was African and Haitian art, which have some religious component and so has meaning, but the materials used in that kind of work, there are a lot of puns, there are a lot of metaphors where power derives from the thing having these characteristics. And so that’s really informed what I do going forward.

So I came up with this Great Bowl O’ Fire and I thought it was really neat. It got a mention on Boing Boing. That was cool. Years later, it got into The New York Times and that sent us about, $50,000 worth of customers or more, which was nice.

And then again, it was in the middle of the business section and generated somewhere between $50,000 and $60,000 worth of orders. People still mention that article to me when they buy sometimes. It was on the front page of the home section, a different fire bowl, but one of my fire bowls, a different design, between Christmas and New Year’s one year, and that was $850 worth of sales because that’s the beginning of first quarter, which is slow for us. Nobody buys anything between Christmas and their tax return. So, timing matters. That’s just an interesting thing, how much timing matters. It should have done better on the front page of the home section, but no.

It took about 2 years to sell the first 50 of those fire pits. And then the following year, I sold about 100. And by the time it really peaked, I was doing about $300,000 a year in sales.

MARK: Three hundred thousand dollars a year from sculpted fire pits?

JOHN: Yeah. Although…

MARK: That you were making yourself?

JOHN: Two-thirds of that was expenses.

MARK: Right. But even so, John!

JOHN: I know right?

MARK: That’s pretty good going. Don’t be modest!

JOHN: I just shipped number 2,200 and a couple more. So that’s how many of these things I’ve made is 2,200 and change. So those really kind of took over.

Anyway, for maybe almost 10 years, there was almost nothing but fire bowls, and I still made the occasional piece of art on the side when I was inspired. But I was really putting all my energy into the fire bowls and the business and growing it because that’s what you do in America, I’ve rethought that. I knew that it probably wouldn’t last forever. So there was always a side hustle I was developing. I’d take the money I made with the fire bowls and spend it developing, say, a mood ring with my friend, Chris Carfi, which instead of telling you what mood you were in, it was a hollow glass-faced ring with little emoticons in it, and you can swap them out to tell people what mood you’re actually in.

We had them made in Taiwan, and they’re really beautiful surgical stainless steel with a glass face. So we spent about $30 grand on that. And we never sold one because they were so high end, we had to retail them at 80 bucks and people are like, ‘I’ll buy this for my kid if it’s like a couple of bucks but my kid is going to lose it.’ And we thought that people in their 20s and 30s would buy them but we were wrong.

So there was that. There was an online commerce software startup that I was consulting with, and they lost their venture funding and I bought a non-exclusive right to the software to try and launch it myself. And it was written on Ruby on Rails and I couldn’t find anybody I could afford to do code so I thought I’d use freelancers. And you know what? You can’t. They warned me but I was sure I can do it. But every time Facebook or Twitter or Instagram or something changes the way they interact with your software, you need to change it ASAP, especially if people are paying for it.

MARK: You’re not afraid to try new things. Even when you’ve got a big success you’re still experimenting and looking for the new thing?

JOHN: Partly because you want to be engaged and interested, partly because you can’t count on anything to last no matter how good it is. I’m the kind of person who’s like, ‘Oh, how hard can that be?’, and then finds out. ‘How hard can it be to be a one-man software startup relying on really busy freelancers who don’t come when you call? Oh, that hard, okay got it!’

MARK: Well you answered that question!

JOHN: Yeah, and I’ll never do that again.

MARK: Okay, but your current big project, you’re really getting back down to earth, aren’t you in a quite literal sense?

JOHN: Yeah.

MARK: Tell us about the Anatomy Set in Stone.

JOHN: Ten years before I started it and I started at about four years ago, I had a massage therapist who wanted to commission a piece of work for a new office. And I was doing a lot of mosaic back in those days. Later I stopped because I just thought it was somewhat difficult to sell. But I had done this piece for him. He’s like, ‘I’d like a mosaic for my office.’ I was like, ‘We should do one of an anatomical drawing because marble comes in exactly the right colors to do that.’ And I made a small piece for him that I still have because he never ended up paying for it. That’s okay. It’ll be in the exhibit that I’m building now.

I had to make it small because of his budget being small. I really wanted to make it life-size and the full figure. And it was kicking around my house for the next decade and I’m looking and I’m looking and it was really good, but it could be so much better. I read this article in The New York Times, a bunch of years back about traveling exhibits for museums and how much museums pay for those and how much they use them. It turns out, it’s a lot cheaper to rent a touring exhibit that’s all ready to go than it is to develop a new exhibit out of your own museum holdings. You don’t have to do all of the research and the planning and etc.

And so a lot of museums, they have their permanent collection, what’s on view, but most of the exhibits that you’ll see that are temporary, are traveling exhibits that somebody has developed and shopped around. And on the low end, according to this article, a 6-week exhibit might make $7,500 or $15 grand. Obviously, if it’s a giant Picasso exhibit at MoMA or something it’s going to be millions. But anyway, I thought I’ve always wanted to do these… What I really wanted to do with the anatomical mosaics is… I chose the easiest of a set of illustrations by Eustachi who discovered the Eustachian tube and was one of the first modern anatomists.

So I had done the easiest one and I thought what if I did the whole set and did it as a touring exhibit? And there are 14 full-size figures in the set that detail different areas of anatomy. It came out of two things that happened. One of them was Stagecoach Music Festival, which happens in the same place as Coachella, it’s a country music festival, they approached me and said, ‘Hey, we’d like you to make a giant mosaic of bottle caps’, which is a thing I pioneered too a long time ago, ‘for our festival’.

They paid pretty well to do this giant American flag out of Budweiser caps, which normally I would not do an American flag but doing it out of Budweiser caps, there was enough room for interpretation and I thought it was an interesting piece of work. But I also knew it would really please the crowd at a country music festival, right. Know your audience, but be a little subversive too so you feel like an artist.

MARK: That’s a good motto.

JOHN: Bury something there for the people who look. So I did this thing and it was an insane turnaround time. The thing was like I think 10 feet high by 14 feet long or something like that. And they only had three months for me to do it. I would have preferred half a year because the cap bottle mosaics, the way that I do do them are very labor-intensive. And if people want to know in what way, go to my website and look, there’s a little video.

Stagecoach commissioned this big thing. And then shortly after I got an email from the Museum of Natural History in New York, wanting to license an image of mosaic I had done years ago of La Sirene, the mermaid, in Haitian folklore and religion. That was part glass, part bottle caps, the tail was bottle caps, the rest was glass. And they wanted to license it for a book about a touring exhibit they were doing. And I was like, ‘Hey, I’d be willing. I don’t have that one anymore. And the photo I have wasn’t great. I would make you a new one if you wanted to put it in the exhibit.’ And so they commissioned it and it is currently touring with their show.

Between doing that huge flag for Stagecoach and then doing the piece for them, and doing mosaic again, after 10 years of maybe not working, and then reading that article about how touring exhibits can make decent money going to museums. And also I was a little worried because I felt like the middle class might be disappearing, and that’s who buys my fire bowls. Poor people can’t afford them and rich people don’t really get them. It’s people in the middle class that support me.

And I’m like if they disappear, I need to find some kind of institutional money like music festivals and museums. Those people are always going to have money, I think, although maybe not as much, the museums, I hear sometimes. So I thought, okay, this is the perfect opportunity to do this giant project I’ve always wanted of the anatomical mosaics in marble. I knew that I could do a credible job of the simpler ones, at least credible if not great. But I didn’t know how well can I pull this off and the only way to find out was to try.

So I ordered a few tons of stone because one thing is if you want consistency through a large piece, you’ve got to get most of this down upfront because even if you buy it from the same store or the same quarry, it’s organic. If they’ve moved 100 feet down the mine, the color is not going to be the same.

MARK: It’s not like you can just go to the art shop and said, ‘I’ll have another tube of that…’

JOHN: No, you really can’t. One of the things that’s great about what I’m doing is because stone is an organic, natural material, even within one box of the same stone, there’s going to be a lot of color variation. And you can use that to your advantage if you do, you know what I mean? You could just treat it as one color, but it’s not and you don’t have to. You can be very subtle. I’m working currently on the eighth mosaic of a series of 14. It was originally going to be 12 because it’s a nice number.

I wasn’t going to do to the detail the skeletons at first because going in I thought, oh, those aren’t going to be as good because I can’t do as much shading as I can with the muscles. But as I’ve been doing the first seven that I’ve finished, that’s of exposed bone and I’ve bought more and more types of stone to work with as I’ve gone. I feel like I’ve really gotten very good at shading the bones. I think it was number six, the rib cage I did for that one, it’s like trompe l’oeil.

MARK: It’s really phenomenal. Obviously, if you’re listening to this, go to johntunger.com and check out the mosaics. And we’ll make sure we got some images and links in the show notes. But it’s phenomenally complex what you’ve done. It’s like a filigree of ribs, and vertebrae, and muscles. And yet you’re using these really big, heavy tools to make it and they’re marble?

JOHN: No.

MARK: How do you actually physically do that?

JOHN: I’ve got a contractor’s Dewalt wet saw that I use to cut 12-inch tiles into strips. And I’ve gotten good enough that some of the stone I can cut as thin as a single millimeter. And when I bought the saw and bought the stone, both the saw company and the stone company told me that’s not going to work. I was like how hard can it be?

MARK: That’s like cat nip for you, isn’t it?

JOHN: Right. Yeah, you just keep telling him what he can’t do and he’ll keep doing it just to show you, which is a favorite line from the children’s book called Wiley and the Hairy Man, South African trickster fable, a great book.

MARK: One of your lines you always used to say to me, impossibility remediation is your specialty.

JOHN: It is because people are like, ‘That’s impossible.’ And I’m like, ‘A) because you think so you haven’t tried. And B) you keep telling me how it’s not possible and I’m going to catch the spot where you’re missing it and be like, ‘But if we did this…’’ There aren’t very many things that are really impossible and maybe people will never fly around without airplanes but they can fly.

A lot of the time, you have to reframe. I can’t flap my arms and fly but damned if I can’t get in a balloon, or an airplane, or hang glider, BASE jumping. There are lots of ways to fly. So anyway, that one was really interesting because it was the first one and before that I did two with the nerves and those were insanely complicated and took much longer and I had to buy new tools.

And the first two or three I did all I used was the saw to cut strips. I had regular nippers I used to break the stone, tweezers for picking things up, an X-Acto blade for nudging things. And about halfway through the third one, I realized I had a really cheap Black and Decker grinding wheel for sharpening knives that I could use to shape the stone a little. It wasn’t made for that but in some ways worked better than some of the things that are made for that.

And then when I decided to do the eyes out of rubies, well rubies have the most hardness of 9 out of 10. The only thing harder than a ruby is a diamond. And somebody gifted me on Facebook two brown sapphires that were already polished that I used for the eyes in the first two. And you can’t cut those with tile nippers or with a carborundum grinding wheel. I ended up holding them up to the wet saw for cutting tile which is horrendously dangerous and stupid.

MARK: Don’t try this at home folks!

JOHN: Yeah, I’m holding with my fingers a little, tiny ruby the size of your iris in my fingers to a very high-speed 10-inch diamond saw blade, but it worked.

MARK: And you lived to tell the tale!

JOHN: Well, an example too of when I said in the beginning, you have to buy all the stone at once, I did not buy enough of the blinding white marble that I’m using for the nerves, because I didn’t realize I was going to need as much of it. And I also thought blinding white marble, it’s perfectly pure white, it should be easy to come by. Not so much it turns out. I bought something from the same quarry, from the same store when I started running out, but it’s got a yellowish tint to it. It’s not the same. But that was good for doing the discs and the spine of this one which are also white, but not quite the same white as the nerve. So I found a use for it is what I’m saying. But I’ve got precious little left to do the nerves and I’ve got to get them all but it’s nerve-racking.

MARK: How many have you done and how many are there left to go?

JOHN: There are seven completely finished. There is one that is very close to done. I have the face, the hand, and below the knees to the feet. I’d love to say that’s going to be done in a couple of weeks, but it’s probably going to take another month. I’ve been on it for about three months, maybe four. That’s the other thing, I thought this project was going to take me maybe two years. And here I am halfway down a little better, one mosaic better than halfway, and it’s been four years.

And I would really like to start trying to book it into museums because they schedule two, three, four, five years out. I don’t want to wait five years when I’m done. But I’m also really glad I didn’t schedule it for two years out in the beginning.

MARK: Yeah, that would have been awkward.

JOHN: It would have been awkward.

I was talking to my friend Austin Kleon the other day and I’m like, I see a lot of people who want to stretch themselves or maybe there’s something they really want to do that they’re just not innately good at. And they’ll bang their head against that wall, over and over and over and if they’re lucky, they get good at it someday. But I feel like the thing to do is, look at what you are good at, and then do that and keep raising the bar. Do what comes naturally to you that’s easy, and then just keep making it harder and harder. And I think that’s a good recipe for doing really good work.

MARK: Yes, apparently cyclists have a saying, ‘It never gets easier. You just go faster’.

JOHN: Right. I don’t think of myself as someone who can draw. I can, but it’s not my strength. That’s not what I focus on. I can take some drawing classes and get good at it, but I don’t need to be good at it to do the work that I like doing. The drawings I’m working from for the mosaics are from the 16th century. Somebody else drew them. What I’m bringing to it creatively is arranging this, but really studying the drawing so closely to be able to do it in stone.

And the thing that’s interesting is that the marble I’m using while not photorealistic is absolutely accurate to the colors in the photos. It’s a little different than the colors in the drawings but it’s truer to the actual meat. And I love that.

I spend a lot of time on hands, feet, the face. If there’s a penis I give that special attention because people are going to look. I also know there are places that just aren’t going to want to show it because, ‘Oh my god, there’s a penis… it’s so inappropriate’. Well, people have them.

And so there is this one penis, it’s just one piece, but it’s two colors and there’s some little moles or whatever in the drawing that I found a piece. I cut it from the middle of a 12-inch tile, but it matches the drawing freaking exactly in one piece. There’s a couple other places where I’ve done that where I really needed it to be just right and I went through 40 or 50 square feet of stone to find a couple inches that were just right.

MARK: John, I hope your dream of having it displayed in a museum comes true so that we can all admire the really amazing attention to detail you’ve got with this by the sound of it.

Obviously we can see images online, but as you said to me, there’s nothing like seeing it full size. So I do hope we’ll get to see that someday soon.

JOHN: One thing I should say I wish I’d gotten that earlier, but what I really want when it exhibits, I want the original drawings hung next to them so that you can compare them because I think that’s much more interesting to compare them than to just see them.

We’re so accustomed to just flipping through Instagram or whatever, seeing so many images for just seconds. I really want to build something that you could spend a day looking at. Backing up and seeing it resolve into a really clean image and then zooming in on the detail and looking. I hope that it will inspire the audience to look as deeply as I had to, to make it, maybe not quite that deep, but to really look and see. I hope it can inspire that. I think people would be well served to spend some time really just looking hard at a thing, because we don’t.

MARK: I’m sure it will inspire. I’m sure it will. John, you’ve taken us on an amazing journey today. Listening to you, I’m really struck how your work and how your business has evolved. You’ve reinvented yourself several times along the way. Looking back, and maybe bearing in mind somebody listening to this and thinking, ‘Okay, well, things are very different from me to when John was first starting out’ – any words of advice to people on this point, fairly early on into the 21st century, but quite mature in terms of where the internet’s taken us.

Any words of advice that you have for how people can carve out their own creative path and maybe in a similarly original way to the way you’ve done it?

JOHN: One thing would be to think about the long term life of what you make. These things that I’m making right now…this is my bid for immortality here, right? The fire bowls because they’re so thick will last hundreds of years and I thought that was pretty good. But we dig up mosaics from Pompeii that are thousands of years old.

MARK: Exactly.

JOHN: There’s no reason to think that these will not. Somebody pointed out there’s no statute of limitations on… people are always interested in people. And these depict people in a scientific manner. Should we evolve to have more arms or something, these will still be interesting because we didn’t used to. They’re like fossils. These should be interesting basically for as long as there are people and they should last about that long. So that’s one thing. It’s always exciting to do whatever is brand new and shiny; 3D printing with plastic or whatever. I suppose in a bad way, plastic also lasts forever, but not necessarily intact if your art becomes microplastic and…

MARK: Not really long.

JOHN: So think about the future and think about the past. When I go to New York City, and I look at all of the amazingly intricate stone carving on old skyscrapers or the cathedrals, like I look at that, and I feel like a hack. And even here in Hudson, just intricately carved stone used to be something we did if we were going to make a building that anybody cared about. We don’t do that now. But I think there is something really satisfying about learning a craft well enough to really make something that will last for centuries.

And I would like to encourage people… I know the temptation is to use the internet as the primary platform for showing your work and you should do that, obviously, but look for real-world opportunities. Look for places where people can see your work life-size and real life, instead of all of the photos being the same size on any given platform and rather small. Look for places where your work can really stand in front of people. And it can be anywhere. I’ll stop.

MARK: That sounds like a great Creative Challenge that we can leave the listener with. So if you’re new to the show, this is one thing I always ask my guests to do at the end of every interview is set you, the listener, a Creative Challenge, something that you can do, or at least get started on within seven days of listening to this recording. And it should stretch you creatively and by definition then, it will stretch you as a person too.

John, your challenge to set the listener is to go out and look for the opportunity that may be out there in the world, the real world around you rather than the online digital space, which is so crowded these days.

JOHN: Yeah, remember, we’ve got a whole planet and it’s pretty big!

MARK: Right.

JOHN: And you can walk out and do it for free.

MARK: You don’t get disconnected.

JOHN: Yeah. The bandwidth is insane! It’s so high res.

MARK: Yeah, wait for it to be downloaded, yeah, surround sound.

JOHN: Great stereo.

MARK: It is. It’s a really good system.

JOHN: I forgot for almost a decade that there was a real world out there and I stopped showing in galleries and stuff because it was inconvenient to move physical objects. But it’s still there. And, honestly, I think, because everyone’s focused on the internet more than anything, there might be more opportunity now in the physical world than there was for a while. I could be wrong about that, but…

MARK: That’s a great challenge, John. If we may be permitted to dip back online for just a moment, your website is johntunger.com.

JOHN: Correct.

MARK: I really encourage anyone who’s listening to this go and check out the amazing images and videos on John’s site. It’s not as good as the real thing but frankly, it’s better than not looking at all. Anywhere else that people can go and engage with your work, John?

JOHN: That’s the main space. I’ve got a store on Etsy. I’ve got things around the web, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook. And my username anywhere would be John T. Unger. But the place where you can get the best sense of what I do and the depth and breadth and the history of it and why I did it would be my site, would be johntunger.com.

MARK: Excellent. So John, as always, it’s been a real pleasure talking to you. I’ve learned a lot. I’ve been entertained by your stories, and I’m sure I’m far from being the only one today. So thank you so much.

JOHN: Oh, thank you for having me, Mark. It’s good to touch base again.

About The 21st Century Creative podcast

Each episode of The 21st Century Creative podcast features an interview with an outstanding creator in the arts or creative industries.

Each episode of The 21st Century Creative podcast features an interview with an outstanding creator in the arts or creative industries.

At the end of the interview, I ask my guest to set you a Creative Challenge that will help you put the ideas from the interview in to practice in your own work.

And in the first part of the show, I share insights and practical guidance based on my 21+ years experience of coaching creatives like you.

If you’d like my help applying the ideas from the show to your own situation you are welcome to join us in the 21st Century Member’s Group.

This will give you access to Goal-setting, Accountability and Q&A videos, as well as other exclusive insights and glimpses behind the scenes of the show. Due to the pandemic, membership is currently on a pay-what-you-want basis.

Your membership fee will also support the podcast and help to make it sustainable.

Make sure you receive every episode of The 21st Century Creative by subscribing to the show in iTunes.

Listening to John and looking at his picture…I thought I have seen this guy before. Then he mentions Hudson. That brought a smile to my face. We are neighbors of Hudson. I really love these discussions. I love his firebowls and enjoy his mosaics intensely. Great talk!

oh, those are fabulous and as he says, will last forever.