Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

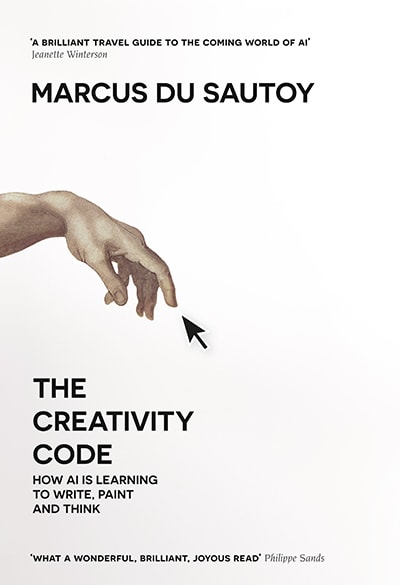

This week’s guest on The 21st Century Creative podcast is the eminent Mathematician Marcus du Sautoy, who takes us on a voyage through the weird and wonderful world of artificial intelligence (AI) and creativity, drawing on insights from his latest book The Creativity Code: How AI Is Learning to Write, Paint and Think (Amazon US Amazon UK).

In the course of the interview Marcus discusses artwork made by AI, how AI can help us be more creative, and whether AI will ever create art that is comparable to human art. So if you’re curious about AI and the creativity – whether you feel optimistic, enthusiastic, sceptical or even fearful about AI – you’ll find plenty of food for thought in this interview.

[Header image photo credit John Cairns]

In the intro to the show I talk about the new company I’ve recently founded, with a new business partner, Mami McGuinness, who also happens to be my wife, and who has recently started practising as a coach. So if you are a Japanese speaker and you are interested in what it would be like to be coached by Mami, you can learn about her coaching service and contact her here.

今回のポッドキャストの最初には、私のビジネスパートナーで妻でもあるマクギネス真美と設立した新しい会社について話しています。現在、彼女もコーチングの仕事をしています。なので、もしあなたが日本語を話すことができて、真美のコーチングに興味があり、コーチング内容などについてもっと詳しく知りたければ、ここから連絡してください

I also talk about the first week of the 21st Century Creative Members’ Group, where I’ve been teaching some principles of goal-setting, and focusing on one type of goal that is very effective to use at a time of uncertainty and disruption like the present.

We have all been sharing our goals for the podcast season, and it’s been very energising to see so much creativity and enthusiasm in the group, especially at a time like this. My own goal relates to the secret new podcast I’m developing for launch later this year.

So if you would like to set yourself a meaningful goal for the next 2-and-a-bit months, and get some encouragement and support from me and the rest of the group, as well as a preview of my new podcast, you are welcome to join us in the group on Patreon.

And in the coaching section of the show, I offer some thoughts on how to stay calm and focused in the midst of the pandemic and the ongoing fallout.

Marcus du Sautoy

Marcus is the Charles Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. As well as conducting his own research he is well known for his work popularising mathematics on television and radio, and via his lectures, newspaper articles and seven books. His awards include an OBE and a Fellowship of the Royal Society.

Marcus’ latest book, The Creativity Code: How AI Is Learning to Write, Paint and Think (Amazon US Amazon UK), is a fascinating tour of the past, present and potential future of AI – and how it relates to games, art, music, poetry and storytelling.

The book also discusses the relationship between creativity and mathematics, and opens up some of the big existential questions relating to AI and creativity, such as authenticity, empathy and consciousness.

As soon as I finished reading the book I reached out to Marcus and he generously agreed to talk to me for the show.

I must admit I’ve always felt a little intimidated by maths – at school it felt very cold and cerebral. So I wasn’t sure what to expect of an eminent Professor of Mathematics from Oxford.

But when I spoke to Marcus he was charming and engaging and he has an infectious enthusiasm for his subject. He really helped me see maths in a new light – as a creative discipline in its own right, and also one that can shed new light on artistic forms of creativity.

This is a fascinating interview in which we explore the current state of AI creativity and how it plays out in games like chess and Go, as well as music, poetry and other art forms. And towards the end we open up some of the big questions about AI and creativity – Marcus shares some very interesting thoughts on whether or not AI will ever be able to produce real art.

Marcus du Sautoy interview transcript

MARK: Marcus, what’s it like to be a mathematician?

MARCUS: I think most people think that as a research mathematician, I must be sitting in my office in Oxford doing long division to a lot of decimal places. And if that were true, I’d be out of a job by now because clearly computers can do calculations faster than I can, but I’ve actually always called mathematics a very creative activity. I really call myself a storyteller, a storyteller with numbers and geometry and I’m not just producing all the true statements about numbers and geometry that are possible. One of my favorite short stories is Borges’s Library of Babel and in the library, there’s absolutely every book possible. And I think many people think that’s maybe what a mathematician is trying to do. But as you know, I’m making a lot of choices about the things that I think are an interesting journey through the mathematical world.

And so, those choices are driven a lot by aesthetics, by an emotional response to the twists and turns of that story. So for me, mathematics is a highly creative subject. It involves that choice. It involves a connection with other fellow mathematicians that I want to take them on a surprising journey, take them somewhere new, engage their emotional world. Actually the book that kind of inspired me to become a mathematician was a book called A Mathematician’s Apology written by a Cambridge mathematician, G. H. Hardy. And in there he really talks about what it means to be a mathematician. And I actually recommend this to anyone to read regardless of where you come from because it really captures the creative side of being a mathematician. He calls a mathematician, like a painter or a poet, but we paint with ideas.

MARK: That sounds very intriguing. There’s one thing in the book, you talk about mathematical proofs or stories being beautiful as well as true.

Would you say that’s a common motivation for mathematicians to find beauty?

MARCUS: The word beauty is used a lot, but I think it’s a much richer kind of emotional engagement than just finding something beautiful. I think you can find something quite shocking. And that’s absolutely a valid response where you thought something was going to happen and then completely the opposite happens. That’s a delightful moment in mathematics. But I think that’s why I feel when people talk about close connection between mathematics and music for example. I often talk about mathematics being the science of patterns and music being the art of patterns. And there again, you can have beautiful music, but you can have music with very many different sort of colors to it. And I feel the qualities that one is enjoying on a musical journey are very similar to the ones I’m looking for in a mathematical journey.

MARK: And you are a musician yourself, aren’t you?

MARCUS: Yes. Interestingly, I fell in love with mathematics and music around the same time. My teachers in school, I was at comprehensive school in Oxfordshire, my maths teacher ignited my mathematical curiosity about 12 or 13 and that’s when my music teacher actually said, “Do you want to learn a musical instrument?” I ended up learning the trumpet and the two have been very close on my professional journey. I still play the trumpet for two amateur orchestras in London, started learning the cello, just about to do a concert with the Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra, exploring how composers use mathematical structures in their composition.

And I think that’s what’s really striking because I spent a lot of time over the last few decades talking to creative artists and time and again, I find that the things that they’re interested in have a structural underpinning that I recognize as a mathematician. And I think that’s a really fascinating thing that I think people think that creative art certainly from the outside is something mysterious. But actually, when you talk to a composer or a visual artist, they will say, ‘No, these structures are really important to allow me to hang my thoughts on it.’ And they’re looking for interesting structures to push them often in new directions that they’d never thought of going in before.

MARK: As I was reading the descriptions of music and mathematics in your book, it made me think about poetic form because at least for traditional poetic forms, there’s a lot of mathematics in things like the iambic pentameter or the sonnet or the terza rima that Dante used. And personally as a practitioner, I use a lot of these traditional forms. I find them very beautiful and in exactly the kind of way you’re describing – just the intrinsic form of the sonnet, I think there is a balance and a natural tension that hopefully gets built up and resolved in the course of the poem. And mathematics has to come into that.

MARCUS: Totally.

MARK: It used to be that poets talked about their ‘numbers’ because they’re always counting the number of beats in the lines. So, maybe it’s not as far apart as it might seem at first glance.

MARCUS: I think you’re absolutely right. And I think it’s almost part of our human species that we’re looking for things with patterns because they help us to navigate our natural environment. And often those patterns or structures that you’re seeing both of interest to the mathematician and used by the artists, they often have a common source in the natural world.

But I think the other interesting thing about structure for an artist is that it can take you in a new direction. Stravinsky always used to say, ‘I can only be creative under huge constraints.’ So, I think that’s the lovely thing about a poetic form, that often you’ll have to think of an intriguing way to say something that you wouldn’t naturally have said because perhaps you’re trying to follow that iambic pentameter or the rhyming scheme of the sonnets and that’s exciting when you’re actually got these constraints, which push you into the new.

MARK: Yeah, that’s very true. Particularly rhyme I think, because when you have your first thought and you think, ‘Oh damn, it doesn’t rhyme, so I’ve got to come think of something else that does.’

MARCUS: Yeah. Exactly.

MARK: It takes you into places that you haven’t thought of and if you do it well then you end up being somewhere that’s surprising to you and also emotionally resonant and therefore, will be hopefully the same for the reader.

MARCUS: I think that’s right. Yes. It’s amazing. Shakespeare for example, was very number obsessed. I only discovered this recently, but you mentioned iambic pentameter, which is, obviously, ten beats. But when he wants you to really concentrate, he disrupts that. So, it’s the disruption of pattern is it? So, the most famous line in Shakespeare ‘To be, or not to be, that is the question’ has 11 beats. So, you suddenly wake up and go, ‘Whoa, what’s going on here?’ And if he’s talking about magic, he uses seven beats. You’re able to use this pattern to be able to almost read something special that’s happening in the text.

MARK: Yeah. And he was doing that against a background – the contemporaries who come just before him had established a very regular iambic pentameter. If you look at Marlowe or Kidd or somebody, it’s much more almost metronomic and then Shakespeare comes in and starts messing about with it more than, I mean everyone was doing it to a degree, but he took it to an extreme, which is one of the things that made him interesting.

MARCUS: Yes. But I think this is going to be the interesting challenge you see when you then turn to something like artificial intelligence and the arts because I think many people’s belief is that artificial intelligence will only be able to recreate what we’ve already seen. So, it’ll be pastiche. How would it ever break out of the idea of just sticking within a particular iambic pentameter? How could it actually have that insight to add a beat? And I think that’s the interesting challenge – can AI take us really into the new or is it just doing more of the same?

MARK: What was it for you personally that you found interesting about AI, artificial intelligence? Why didn’t you just stick to more traditional fields of mathematics? What was the attraction of AI?

MARCUS: I think that we’re all intrigued at the moment about how much AI can do because we’re really going through an AI heatwave. We’ve had these things called ‘AI winters’ where nothing seems to really work but suddenly the last few years there’s been a real step-change.

And I think for me, what suddenly got me interested in this area and which actually was the spark for writing this book was seeing a piece of code be created for the first time. This wasn’t in the arts, but actually within the confines of a game. A piece of code was created to play this ancient Chinese game called Go, which is played on a 19 by 19 board, grid. You put black and white stones down and try and surround your opponent’s territory before they surround yours.

And this was always traditionally regarded as a very hard game to code up because when you play it, there’s a lot of pattern recognition on the board, which is quite hard to articulate why you’re doing something, a lot of intuition, a lot of creativity. But what has changed is that code in the past was written in a very top-down manner so that somehow the human who wrote the code had to know what to tell the machine what to do. So, we had to sort of really understand it.

But code now is being written from a bottom-up way, something called machine learning and this allows the code to change and mutate as it encounters new data. So, in the case of this game, it was given human games to learn on and then started playing itself, making synthetic games. And through its playing, it changed the code to try and optimize certain moves that you could see were being very powerful.

But then when it played in a match against one of the best humans we have, Lee Sedol, what I saw was it suddenly making a move that nobody had expected at all. It’s now become famous. It’s called move 37 in game two of this match. And what happened in this game because this piece of code played a move that all the commentators, when they were commentating on the match said, ‘Wow, that’s a really weak move.’ It laid a stone on the fifth row in from the edge and early on in the game, that’s considered a really weak move. And all the commentators said, ‘Well, the human should be able to win from now.’ But in the end, it turned out that that move, though very late on in the game meant that the piece of code – AlphaGo, it’s called – actually controlled large swathes of territory and it won the code the game.

So, for me, this is very interesting because I think that’s what I’m looking for is something, a surprising move where everyone was kind of shocked by it, but something which ultimately has value. You don’t want just surprise for the sake of it. You want value. And now, you can judge those things very nicely in the confines of a game but you see, if a human had written that code, a human says, ‘You shouldn’t play that far into the board on the fifth row in.’ The human would have written a piece of code saying, ‘Don’t make that move.’

And for me, what was so exciting was seeing this code actually find a very powerful move on its own from its learning process, a move which humans now incorporate into the playing of the game. We have been pushed into a new way to play this game. And for me, that was a really exciting moment and I realized, hold on, okay, if this is just a game, where else can this kind of learning process of code encountering data take us into somewhere where we’ve never even thought of going before? And so, that was the beginning of my journey of this book. What about if it considers the visual realm, the musical realm, the written word or even mathematics – could it perhaps make move 37 in game two in any of these realms and actually show us new ways to do things?

MARK: So, before we go on to look at some of those questions, I really want to underline this for anyone who’s coming to this afresh, that it was literally a game-changing move. It was unexpected. It had the criteria of novelty and value, which is more of the classic definitions of creativity. And it came from the machine learning by itself.

This wasn’t something that had been programmed in or could be predicted by the programmers. It thought this up by itself, so to speak.

MARCUS: That’s right. And I think that’s the game-changer as you said, that this is why this new sort of code which can take data and see something new in it and help us to change our behaviours. I think as creative artists and I’ll count myself in there as a mathematician, I think that we can get very stuck in particular ways of doing things. We find something that’s quite successful and we repeat that behaviour. You’ll see that in musicians who will have a particular style and they’ll get a bit locked into that style. And so, actually, we start behaving more like machines, just repeating behaviours. And the exciting thing is I’m seeing in the stories that I’ve looked at in this book that this new tool of artificial intelligence, which often it’s a story told with a very dystopian take that it’s going to wipe us out. Now, I don’t see this as a competitor. I see this as amazing collaborator in the creative process actually helping us as humans to behave less like machines and perhaps show us new ways to do things. So, I think it’s an extraordinarily powerful tool for a creative to actually suggest new ways of looking at what we’re doing.

MARK: Could you give us some examples because you’ve got some really extraordinary stories in the book of AI as applied to artistic creativity. Quite often it’s the chess champion beating or the Go champion beating stories that make the headlines. But can you give us an idea of if anybody’s thinking, ‘Well, that’s all very well for games, but I’m an artist, I’m special.’

MARCUS: Yes, exactly.

MARK: Give us some examples that might show us a different way of looking at that.

MARCUS: Let’s take music to start with because music has got a lot of pattern in there. And of course, if you turn on the radio and you hear a piece of music, you can probably identify perhaps who the composer is if you’ve listened to a lot of music because they have particular styles. So, that’s something that artificial intelligence is very good at spotting, the key characteristics that make up a style. I tell a story of a jazz musician who had a very particular style, Bernard Lubat. He’s a jazz pianist. And when you hear him improvising, you’re probably recognize if you know his kind of style, ‘Oh, yes, that’s him.’ Sony Labs in Paris developed something called the Jazz Continuator.

And this piece of AI listened to the pianist playing away and started to analyze statistically the patterns that he was making with the notes. And then was able to start playing live with him in a call-response manner. And interestingly, an audience was challenged with listening to this and was asked to see if they could identify the human from the AI. And often, they attributed the human to the AI because it sounded more complicated and richer exploration. And this was Bernard Lubat’s response, he said, ‘Wow, gosh, well, that’s amazing. I could have played like that, but I’ve never ever even thought of playing like that.’ But the weird thing was, he said, ‘But I recognize that world, that sound world is my world.’ So, in a way, this wasn’t pushing into the new, it was just showing Bernard Lubat new things that he could do with his material.

So, it wasn’t asking him to become a completely different musician, it was just saying, ‘You know what? You’ve got kind of stuck in a particular way of playing.’ It’s as if he was playing in the corner of a room and only the corner was lit and suddenly the AI lit up the whole of the room and said, ‘Look, there are many other places you could explore with your sound world.’ For me, that’s a very exciting story because it’s a tool that was used to expand his repertoire.

MARK: I love that story, that was one of the standouts for me. I remember thinking, what would it be like to be Bernard Lubat when he’s hearing that? It must’ve been quite eerie. His reaction I thought was as interesting as the story itself, of what the Continuator could do, because he could have felt threatened, and if he was not a confident artist, maybe he would start critiquing, finding fault or whatever, but actually he embraced it. He said, ‘Actually this can make me better. It can open me up. It shows me myself from a different angle.’

MARCUS: Yes, exactly. I think this is the point. Often when I show people images and then I say, ‘That’s been painted by AI,’ for example, I think their first reaction is they feel very cheated because of course, actually, when you’re encountering a piece of art, the feeling is you want to have a conversation with the artists, with another human being, with another consciousness, another way of seeing the world. And then you say, ‘Oh, that’s being made by AI.’ And you have that feeling of being cheated. But then again, if I tell you a joke and you laugh at the joke and then I say, ‘That joke was actually composed by a piece of artificial intelligence.’ That doesn’t invalidate the laughter that you just went through.

So, it’s interesting that response to a piece of art and then the need to know actually the source, the story behind how it was created. But again, you’ve got to remember that a lot of these tools that are being used, they’re taking human data to learn from. In a way, this is just a filter or an exploration of the emotional world that we’ve created in our art. It’s not surprising that what it’s producing we’re having an emotional response to it because it’s learned on our emotional world.

MARK: Interesting. I did have that experience. There was one section, obviously, I honed in on the poetry section of the book and there’s a wonderful website you introduced me to called ‘Bot or Not’ where it shows you a poem and you have to decide, was that written by AI or was it written by a human?

MARCUS: Yes.

MARK: I took the 10-question test and there was one poem that fooled me that it was by an AI and I thought it was a human, was a very short joke. And it was a silly joke, but it made me laugh. And I think probably because I laughed, I thought, ‘Oh, that’s got to be somebody fooling about.’ It looked artless and silly, but actually that was, I think it was compiled from Google predictive texts or something.

MARCUS: Right. Yes.

MARK: So, that was really quite an interesting experience taking that test. And I think a lot of this maybe applies to audiences rather than the artists themselves. You have a wonderful description of David Cope when he comes up with a fake Bach symphony with his program. I can’t remember what it was called.

MARCUS: Aaron. Yes.

MARK: He managed to fool some quite well-educated audiences didn’t he?

MARCUS: Yes. That’s very interesting because I had done a similar exercise actually here in London in the Barbican of this year. And what I did was to get a piece of AI with Ph.D. students. We got the AI to learn on Bach and Bach of course, is great to learn from because there’s so much pattern in there. I talk in the book actually about the kind of algorithmic way that Bach often wrote. He actually composed something called the Musical Offering and wrote it as a set of little algorithms. You have to solve these puzzles. You’re given one line of music and there’s a weird sort of clef upside down at the end of the music and you realize, ‘Oh, actually I’ve got to play this twice, forwards and backwards at the same time.’

Bach has a lot of kind of code already in his work, but what we did was we created a piece which was one piece, but it went in and out of Bach and AI. You were never quite sure as you were listening to it. Some of it was human and some of it was AI. So, it wasn’t just a simple dichotomy. And then we asked the audience to vote with cards throughout the performance of this four-minute piece when they thought it was human and when they thought it was AI. And the audience just found it almost impossible to, there was no clear moment when everyone said, ‘Oh yeah, this is clearly not human.’ But the one person who could tell was Mahan Esfahani, who was the harpsichord player.

He said, ‘I know exactly the moment it goes to AI because suddenly it becomes really difficult to play.’ And this is fascinating because of course, the AI doesn’t care about embodiment. It can write notes but it doesn’t have to play them. Bach was a master at writing wonderful music, but also music that could be played very nicely with the fingers; the fingering was important. So, this is a really interesting point which separates often AI art and human art is the question of the embodiment. I’ve seen actually that AI often becomes overcomplicated in some sense because it can cope with complication. Even with Bernard Lubat and the jazz Continuator, the jazz Continuator was starting to get overcomplexity that actually Bernard Lubat would actually find it quite difficult to reproduce what the AI was doing.

And this is interesting because we have our sensory equipment to engage with the world around us, our eyes, our ears, our sense of touch, smell, and this limits our engagement with the world such that the art that an AI might produce might actually push the complexity such that we as humans are finding it very difficult with our sensory equipment to engage with this.

And actually one of my favourite AI films is Her, which is the film where… so you’ve seen this film before? If anyone has not seen this, it’s a great film. This guy splits up with his girlfriend or something and the chance to have an AI girlfriend for a while. And so, he sort of engages with this thing online, of course, falls in love with the AI girlfriend. It’s so good at pretending to be real.

But the wonderful moment for me is when the AI girlfriend dumps the human and says, ‘Oh, you humans are just so slow. It takes ages to interact with you. I’ve got to know millions of AI online in a split second where we’re going excitingly into the new.’

And that, for me, revealed something which I think is going to be very striking as we go forward. That as AI becomes more and more sophisticated actually it will probably only enjoy interacting with other AI and it will look at us humans probably as we humans look at a forest or mountains. They don’t seem to change, mountains… but if you did speed up time, of course, mountains are very dynamic things. So, it’s interesting that questioning embodiment is really important I think for this human/AI interaction.

MARK: And also I’m wondering, listening to you talk, whether there’s a fundamental difference in the way audiences respond and creators respond because…

MARCUS: Oh, that’s very interesting. Yes.

MARK: …one of the things, the constant themes in the various stories is people feeling cheated or angry, or there’s a wonderful description of delighted horror among the classical music buffs when they realize they picked the wrong Bach as the real one. But then the artists and the musicians, they seem to be more interested in, ‘Oh, great. Well, technically, this is a really interesting thing.”=’ Like, ‘It’s impossible to play that on the harpsichord.’ Or Bernard Lubat looking at,’This is showing me new possibilities.’

Do you think that maybe the audiences and readers might look at things more romantically than the actual practitioners themselves?

MARCUS: Yes, and that’s partly why I wanted to write this book and show people that actually a lot of creative process has a kind of, there’s a lot of mathematics in the creative process that people looking for kind of rules, patterns, structures.

And I think there’s a terrible romanticization of the creative act, that it’s all about expressing emotions or it’s all deeply mysterious. And when you talk to a practitioner, I remember doing a program about Phillip Glass and Phillip Glass saying you know, ‘People find my music very emotional, but I don’t write the emotion and the emotion comes out of the structure. I write these interesting patterns and algorithms and then the emotion appears.’ And I think that for me, it was one of the points of the book was to show people that a lot of the creative process has these rules and therefore, those rules are things which are interesting because they could be implemented in code and you can see where else you go with them.

But I think your point about the audience is very interesting because I think that’s why when you talked about the poetry test, why poetry perhaps can trick you more easily than many other forms. When a poet writes a poem, they often want to leave room for the audience to bring their own bit of creativity to the reader. You don’t want everyone to have the same response. And so, that’s why I think, especially poetry has a lot of space. It’s a conversation and this is a conversation between the reader and the poet and the reader will bring some of their own creativity to the reading of that poem. If you’ve got something written by a piece of AI often it can pass an AI Turing test. The human will think it’s human-written because they will bring a lot of their own response to that poem.

MARK: That’s a really interesting point. I’m reading Don Patterson’s book The Poem, how poetry works. And he says, ‘Poetry is as much a mode of reading as it is of writing.’

MARCUS: Very interesting, yes.

MARK: So, if we treat something a bit like Duchamp’s Urinal, if we treat it as poetry, then it becomes poetry because we’re looking for significance in it. And obviously, I was looking at this, the ‘bot or not?’ test and thinking, well, it works on some kinds of poetry, but other kinds, I don’t think it does. So, the stuff that I think is most susceptible to that is the kind of very fractured, gnomic, modernist type of verse that to put it bluntly, doesn’t always seem to make sense, but you are supposed to look at it and just find something deep in it. And it works for nonsense verse because again, the disjunction is part of the charm. It doesn’t need to hold together. It could work for surrealism. I think it worked on me with a joke. I don’t think it works on anything where you want more coherence and a sense of –

MARCUS: That’s right. Yeah, I think you’ll see, I was very struck actually in writing this book, which art forms is AI being most successful in? And it struck me that the visual world, it is actually being very successful. This machine learning has produced tools which can recognize images now. That’s quite a big challenge. You’d give it a picture to be able to decode what’s relevant, what’s important and say what’s in the picture was always a huge challenge for AI and now this learning process has allowed AI to recognize images very clearly. And so, it can now also generate them. Music as well because there’s the patterns in a particular kind of…it’s a sort of closed form, a bit like a game, of course, it connects to our emotional world.

But the spoken word is, I was quite surprised how actually AI is still really struggling with the spoken word, the written word, spoken and written. Well, both, actually. I think it is partly it can do short forms like a poem and actually I got 350 words in my book is written by a piece of artificial intelligence and it was so successful that nobody’s identified those 300…

MARK: I haven’t spotted that and when you read that I thought, gosh, I wonder wherever that was.

MARCUS: Well, don’t worry. Not even my editor has spotted it! Which I find deeply depressing, surely because I think it looks terrible, it reads terribly and just what a poor statement it is on my own writing.

But one of the things I think here is that of course language and writing is so much more than just the words. So, the AI might be able to know the definition of the words, but the context of that whole thing, there’s cultural context, historical context. And there are things called Winograd Challenges which are given to an AI if it’s trying to pass the Turing test because it’s very difficult for an AI to sniff out what a particular word might refer to whilst we will be able to see the context very clearly.

If I say, ‘The government banned the demonstrators from marching because they feared violence,’ you know that ‘they’ refers to the government. But if I changed that to ‘they advocated violence,’ that ‘they’ refers to the demonstrators. Now, an AI just is completely thrown by that because you need so much historical context for that, to know that demonstrators might be violent or the government might have some fear. So, that’s really interesting that the written word, spoken words, I think it’s depending on a lot of years of evolution in the human brain to develop language and it seems quite hard for the AI to fast track that. So, novelists out there, you’re safe I think!

MARK: For now.

MARCUS: Yeah, for now.

MARK: Because a lot of things you talked about is that longer narrative arc that it’s hard for the artificial intelligence to do. And I think in poetry it’s the bigger conceptual arc in a poem likes, and I’d say ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ or ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ – you’re not going to get anything as coherent as that as yet from an AI.

But even in the music chapter, you conclude that AI can churn out muzak but not quality music.

MARCUS: Yes, I think that’s right. You see the Jazz Continuator, for example, it’s quite fun to listen to it for a few minutes, but after a while it just becomes boring. I could not listen to an hour of that because I don’t feel it’s really going anywhere.

So, it’s very interesting that I think something which has a temporal element to it, AI can do local generation of something interesting but still not the global. Which is interesting because you can use that as a tool, as a creative to perhaps stimulate you to go in a new direction, but then you will then piece those together to make something which has a global coherent narrative.

MARK: You have this lovely phrase; you say at the moment they are telescopes and… is it tools and telescopes rather than authors when it comes to this sort of thing?

MARCUS: Yeah. Exactly. Suddenly, we’re able to see distant planets that we could never see before. So I think that is the exciting thing. We’ve got this as a tool to examine data more deeply, find things that we’ve missed in there. But I think it is a tool… I think it’s a little bit like when suddenly the camera came onto the scene to be able to suddenly see the world around you through this filter in a different way and explore what could be done with it. It isn’t just simply about reproducing what’s there. As Paul Klee said, ‘Art doesn’t reproduce the visible, it makes things visible.’ What I’m hoping is that these people will find that this AI tool for creativity can make things visible that we weren’t seeing before.

MARK: Okay. So, that’s where we’re at currently. What about the future? Given the capability of machine learning to surprise us, move 37 in game two, what do you think?

Could it evolve to the point where AI could create art? That we would say, actually that is comparable and indistinguishable on a bigger scale or even a more moving scale to humans?

MARCUS: I think that you’re already seeing creative acts by a computer that are pretty convincing and people are taken in by. But I think really this is only going to become interesting when AI needs to say something to us. And for me, where does the urge to create art come from? I think it’s because it’s a quality of us being conscious that we have an internal world that we want to explore our own internal worlds and we use our art as an exploration of that. We want to share the way we see the world and explore whether others see the world like that or perhaps we feel we’ve got a new way to engage with our environment. We want to share that. Carl Rogers describes creativity as exactly that. The examination of the internal world.

So for me, I don’t think this is really going to be interesting until AI has its own internal world. And it suddenly has a need to express that, I use the word later on in the book, intentionality. Where is the intention coming from? That piece of code that played that game didn’t want to play that game. It was the human that sets it on the game and it played the game very well and it saw its goal. It had a goal which was to beat its opponent, but the intention was still coming from a human.

And I think once consciousness emerges in code – and I say ‘once’, I do think it will, I don’t know how long it will take, but I didn’t see a reason why it shouldn’t. We are just a bunch of atoms put together in a very complex way, developed over millions of years of evolution and it caused us to have this internal sense of ourselves. I think there will become a moment when that will happen in machines.

I make a little speculation in the book that I think that our drive to be artistic and our sense of consciousness I believe could well have occurred about the same time, maybe 40,000 years ago. That’s when we see the human species starting to explore art for its own sake, drawing things on the walls, it’s not utilitarian. Those hands on the wall are an existential expression. ‘Here I am’, they’re saying.

So, I think that really this is only going to become interesting when AI has an internal world. However, in some ways I would say that’s already perhaps beginning to emerge, not consciousness certainly, but we are developing code that because it’s changing, mutating, learning, becoming very different from what the human originally wrote down, this code, we need to have ways to examine quite how it’s thinking, how it’s seeing the world, how does it make its decisions? Because after all, we’re being pushed and pulled around by algorithms. And so, as we go forward, we’re going to need tools to be able to really understand why it’s making those decisions. I think some of the most interesting art projects from AI aren’t actually about creating art that we humans think are interesting. They’re about creating art that can help us to understand the internal decision process of the code.

It’s almost as if code has got its own subconscious now because it’s so complex, the code of the machine learning process that when we look at it, it’s too complex for us to navigate quite how it’s making its decisions. Some of the most interesting stories in the book I think as far as art are concerned, are helping us to understand the code. So, my favorite one is actually something called DeepDream. And actually you gave me a challenge to think of something that people can try out after having listened to this and explore using perhaps AI for creativity. And this is the one I’m going to offer people because it’s something called DeepDream, this is a project that Google developed.

They said, ‘Okay, look, we have an amazing image recognition software. Give it an image, it can recognize what’s in that image,’ but what is it really seeing? So, they decided to reverse the process and they gave it a random load of pixels or an image which didn’t really have anything clear in it. And just asked the software to accentuate anything it was seeing in that image. And this allows us actually to see how the code itself is seeing what, how it’s learned. When you do this, what’s extraordinary is you start to see lots of animals emerging within an image. Lots of eyes, lots of faces because this is what the AI has been given to learn on the data that is learned from, lots of mechanical things.

I gave it a picture of a string quartet I play for. And when it went through this filter, suddenly the first violinist turned into a leopard and the other three of us, I play the cello in this quartet, turned into a motorcar. And it was very interesting sort of seeing this, but this has been used for example, to show bad learning that’s occurring in code. For example, DeepDream was given kind of grey pixel background and started to see dumbbells appearing inside these images. But weirdly, the dumbbells that appeared always had arms attached to them. Why? Because the software had only ever seen images of dumbbell was being held by strong men and women. And so, it thought it was part of our anatomy. It hadn’t ever seen a dumbbell on its own.

So, this kind of art is helping us to see when things are going wrong that it’s actually not learned properly. And I think this is really striking because I did an event last year with a woman from MIT Media Lab, she’s a roboticist and she told me the story of how she’d had some robots delivered to the lab and she’d opened them up, switched them on, and they had some vision recognition software to see when somebody was in front of the robot. And when she went in front of them, it didn’t see anybody there until she put a white mask on. And then suddenly these robots started responding. She was a black woman. And so, she lifted up the kind of bonnet of the software and understood that the code had only ever been given pictures of white men to learn on.

MARK: Oh dear.

MARCUS: Using these artistic tools as a way to explore the way a piece of code might be thinking might really be a powerful tool for us going forward to make sure that we keep control. So, actually my challenge for creatives is, because it’s quite an easy thing to experiment with, but it’s a visual challenge but to take an image and to upload it to this thing called DeepDream generator. And you can then try and use this tool to augment the image and it’s almost a conversation with a piece of code so you start to see the image changing, mutating. And so, I think it’s quite an interesting experiment just to interact with code, see how code is seeing your image, how it would change it, and whether that gives you any ideas for your own perhaps visual generation to see whether it’s helping you to see things in a new way.

So, it’s quite fun. It’s quite simple to use. But the challenge is what images actually do you have an interesting conversation with this piece of AI and what images somehow don’t work for this. So, I hope people might have fun just trying to… I enjoyed playing around with it and I felt like, ‘Wow, the art that is coming out of here is helping me to understand a bit more deeply how an AI is working.’

MARK: That does sound terrific fun. So, that’s Google’s DeepDream?

MARCUS: Yeah. So, the website they need to go to is called deepdreamgenerator.com.

MARK: Great.

MARCUS: And then they can try and play around with the tools that are there.

MARK: Okay, great. I’ll make sure there’s a link there in the show notes. And you know, I was thinking about the poetry question. I thought, ‘What is it that would make a real AI poem?’ And I was thinking about Thomas Hardy’s quote about poetry. He said, ‘The poet wins our heart by showing us his own.’

Maybe DeepDream would be the start of a window into the AI’s heart. And who knows what could emerge from that in time?

MARCUS: I think that’s really interesting because I think a lot of artists are interested in exploring things that are impacting on society and making a statement about them. And I think actually treating AI as the art is a really fascinating project. We need tools to examine this changing world and the interaction between AI and the creative world will be really important dialogue as we go forward.

MARK: Marcus, thank you so much. This has been a really mind-boggling conversation. I think I’m going to listen to this several times to get my head around some parts of it. I’m sure I won’t be the only one among my listeners. The book, The Creativity Code: How AI Is Learning to Write, Paint and Think (Amazon US Amazon UK) is a really fascinating exploration of these themes. If you’re listening to this, and you found this conversation interesting, there’s plenty more in Marcus’s book.

Marcus, is there anywhere else that, do you have a website or somewhere that people could go online and engage with your work further?

MARCUS: I have a website, it’s www.simonyi.ox.ac.uk. Simonyi is the professorship that I hold. This is Charles Simonyi who actually was one of the first to start developing code with Microsoft and he’s endowed a professorship called the Professor for the Public Understanding of Science. So, people can go there and that has a lot about all my other activities interactions with the musical worlds, artistic worlds, a play that I’ve written and some information about other books and articles that I’ve written. So, hopefully, people enjoy exploring my creative outputs there.

MARK: Excellent. And again, I’ll make sure that is in the show notes. Marcus, I think you’ve done a lot today already to further the public understanding of mathematics and AI. So, thank you so much for your generosity and insight today.

MARCUS: Well, it was a pleasure talking with you.

About The 21st Century Creative podcast

At the end of the interview, I ask my guest to set you a Creative Challenge that will help you put the ideas from the interview in to practice in your own work.

And in the first part of the show, I share insights and practical guidance based on my 21+ years experience of coaching creatives like you.

If you’d like my help applying the ideas from the show to your own situation you are welcome to join us in the 21st Century Member’s Group.

This will give you access to Goal-setting, Accountability and Q&A videos, as well as other exclusive insights and glimpses behind the scenes of the show. Due to the pandemic, membership is currently on a pay-what-you-want basis.

Your membership fee will also support the podcast and help to make it sustainable.

Make sure you receive every episode of The 21st Century Creative by subscribing to the show in iTunes.

And now, you can judge those things very nicely in the confines of a game but you see, if a human had written that code, a human says, ‘You shouldn’t play that far into the board on the fifth row in.’ The human would have written a piece of code saying, ‘Don’t make that move.’

“Case in point: In 1996, Adrian Thompson of Sussex University used software to design a circuit by applying techniques similar to those that train deep networks today. The circuit was to perform a straightforward task: discriminate between two audio tones. After thousands of iterations, shuffling and rearranging circuit components, the software found a configuration that performed the task nearly perfectly.”

-Is Artificial Intelligence Permanently Inscrutable?