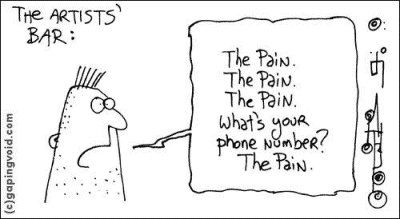

Drawing by Hugh MacLeod

The tortured artist is one of the great cliches of creativity. And like all cliches, it contains a grain of truth.

Look at the work of any truly great artist, and you will find suffering is one of the big themes – whether it’s the everyday misery of poverty (Dickens), the pain of unrequited love (Petrarch), the atrocity of war (Picasso), the inhumanity of bureaucracy (Kafka), the pathos of passing time (Hardy), despair in the face of death (Tolstoy), or sheer existential anguish (Plath, Munch).

Even apparently trivial forms of popular entertainment, like the cinema and pop music, have produced masterpieces of suffering, like Bowie‘s Low, Joy Division‘s Closer, or just about anything by Kenji Mizoguchi or Leonard Cohen.

Is this surprising?

Not if you think the Buddha had a point when he said suffering is an integral part of life – and if you agree with Hamlet that art should hold “the mirror up to nature”. So if you want to be a great artist, sooner or later, you’re going to have to deal with suffering.

There are two ways to do this: in your life and in your work.

Firstly, when you encounter suffering in your own life, don’t shy away from it. Look it in the eye. Even in the midst of a disappointment, a betrayal, an illness, a broken heart, or even a bereavement, there should be a part of you that observes and pays attention. That thinks “so this is what it is like” – and remembers.

Graham Greene said “there is a splinter of ice in the heart of a writer” that forces him or her to look when others look away. To make notes. To record and tell the story.

Secondly, when you’re working and you come up against a creative block, ask yourself whether you are shying away from dealing with painful emotions or experience. If so, then the challenge is to stick with it – to stay with the pain, the suffering, the embarrassment, whatever it is – until you make a breakthrough.

Of course this risky and scary. And when you try to deal with a big theme like suffering, it’s so much harder to maintain high standards of artistry. You can be so overwhelmed by the subject matter that your craftsmanship suffers. There’s a dangers of becoming sentimental or ridiculous.

But great artists don’t become great artists by playing it safe.

And How Not to Do It

Everything I’ve written so far has been about what I would call genuine suffering – the kind of suffering that’s part of life itself, which no true artist can avoid.

But there is also another kind of suffering, that’s all too familiar to those of us of the artistic persuasion (and our friends and family).

This is the kind of self-pitying, self-dramatising, maudlin ‘suffering’ that gives artists a bad name.

It’s the kind of suffering that makes us tell ourselves there has never been a more sensitive, talented, unlucky and unjustly ignored creator than us.

It’s the kind of suffering that sends us to bed (or to the bar) for three days when we get a bad review, or when we are passed over for an award, or when we receive some other slight to our professional pride.

It’s the kind of suffering that makes us moan and whinge and bitch to our partner, best friend, family, blog readers and/or Twitter followers, until their patience is stretched to breaking point.

This kind of suffering should alert us to the fact our old friend the Inner Whining Artist is on the prowl again – and it’s time to tell him/her/it to leave us alone so we can get on with our work.

Let’s face it, we all indulge in this kind of suffering from time to time. Some days, it’s hard to separate the two types of suffering. But it’s essential that we keep trying.

If we’re serious about making real art, that is.

How about you?

Do you recognise the two types of suffering for your art?

How do you get yourself to face up to the first kind?

How do you stop yourself from indulging in the second kind?

About the Author: Mark McGuinness is a Coach for Artists, Creatives and Entrepreneurs. For a free 26-week guide to success as a creative professional, sign up for Mark’s course The Creative Pathfinder. And for bite-sized inspiration, add Mark on Google+.

I found this post extremely funny.

I think one reason people do not always see the “inner whining artist” in themselves is that we tend to know someone who is the absolute extreme caricature of the type, someone whose concept of himself as so very different from others (sometimes indicated as “the masses”) seems both quite false and incredibly egotistical.

But just because someone else is an extreme version doesn’t mean there cannot also be a small and quieter whiner in any of us.

Glad someone shares my dark sense of humour. 😉

Yes, just because we don’t all go to extremes, doesn’t mean the IWA isn’t on the loose.

Great post as always, Mark. I’ve never really liked the tortured artist stereotype, mostly because of the stereotypical drinking and drug use that tends to go along with it. I’m really tempted to tell such artists to pull up their Big Girl/Boy panties and get on with their creative endeavor.

However, I do think that whining and kvetching privately is one way of dealing with our disappointments, whether in art or general life. Sometimes this leads to creative breakthroughs or a resolve to do better next time. Limiting the kvetching to a particular amount of time (a day or two for minor disappointments, a week or so for somewhat bigger things) should keep artists from bogging down in a torture of their own making.

I think there needs to be an exception made for really huge life-changing events, which can derail an artist and take years to overcome.

Yes indeed, we all need to get things off our chests from time to time. And I agree with your point about life-changing events.

And I wouldn’t say either of those fall into the category of the ‘wrong kind of suffering’. The IWA specialises in making things worse than they need to be, by adding a layer of self-criticism and/or self-pity on top of the ‘genuine’ suffering we experience.

Hi Everyone,

Thanks Mark, you always make me smile. I like the depth of your writing and also your sense of humour. Suffering is difficult no matter how we try and gloss things over or avoid it. I was thinking the other day about my mother who has said from the beginning, with forceful intensity, about my art career, ‘Simon you will never earn a living from your art’.

This hurts me, mostly because I hear a hopelessness in her words. To be surrounded by hopelessness in many areas of life, is what causes me most suffering, and makes things most difficult. But you know what…it makes me stronger and more determined to prove that it is possible to make a good living from my art. I know without a doubt, that hope abounds, no matter how dark things get.

So when creative people show non creative people (like my mother and others) a new and very different vision of hope filled possibilities, it sets those types of people free to believe in something greater than themselves. For me, this is the greatest service a creative person can offer a world that is starved of hope.

Great topic Mark, thanks.

Simon

Thanks Simon, that’s a very inspiring way of looking at it. The complete opposite of the Inner Whining Artists!

Excellent Insight. It was a treat to read this post.

Thank you!

Great post, it is a very important issue to find how oneself should seize every moment into creativity, whether is a happy or a dramatic moment.

That’s right, it’s all grist to the creative mill!

I enjoyed this and I shared it further…not with certain people who inspired the question that ended in your book, though – they’re used to loving themselves for loving somebody. 😀

Basically, in a world we have today: with access to everything, an OK to excellent quality of life and less spontaneous socialisation; everyone can be stereotyped by everyone else. For example, there’s someone who thinks I am a pathetic starving artist. There’s someone who’d think the same about you, one of your readers or some person on one of the art-centered social networks. With no graspable “normal”, it’s easy to be a jerk in the eyes of someone with different standards and values.

So it’s a good job we know what’s normal. 😉

The first type of suffering propels me on to further creativity. Writing about obstacles helps me overcome them.

The second type of suffering is my way to deal with self doubts, which are harder to overcome – at least for me. I deal with this by following the Beatle’s advice: “Let It Be.” I just do the best I can at that time. It’s not perfection.

Yep, the proof of the pudding is what we do as a result.