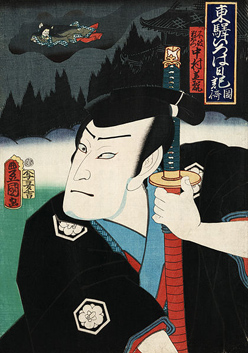

Kabuki star Ebizo Ichikawa XI in action, from Ebizo’s YouTube channel

Last Christmas I visited the Kabuki-za theater in Tokyo to experience kabuki—one of Japan’s traditional forms of drama, dating back to 1603. As the curtain slid aside, it revealed a world of breathtaking beauty: a stage like a painted scroll, where actors in bright costumes and makeup acted, sang, danced, and fought. In one play, a riotous samurai battle climaxed with spectacular acrobatics. In the next, a lover driven mad by separation danced with a hallucinated vision of his former sweetheart. It was as though a book of prints by Hokusai or Hiroshige had come to life in front of me.

The actor playing the crazed lover is called Ichikawa Ebizo XI. This is his actor’s title, not his birth name. Why “the eleventh”? Because he is the eleventh member of the Ichikawa family to bear this title, most of whom have been blood relatives, with others inheriting the name via adoption. Ebizo’s father was Ichikawa Ebizo X, and his grandfather Ichikawa Ebizo IX. The lineage stretches back to Ichikawa Ebizo I, who trod the boards in Tokyo, then called Edo, in the 17th century.

Ebizo I was the originator of the family’s signature aragoto style, a form of acting in which the actor uses bold costume, makeup, and gestures to portray warriors, gods, or demons. The name Ebizo is awarded when an actor is deemed to have earned it through his mastery of aragoto. The current holder first took the stage at the age of six, and was awarded the title at 26. One day, if he makes sufficient progress, he may earn the even more prestigious title of Ichikawa Danjuro XIII — the name Ichikawa Danjuro XII having been held by his father at his death in 2013.

Just like the Elizabethan theater, the female roles are played by male actors, women having been banned from the kabuki stage by the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1629. Watching Ebizo dance, I was aware that his lover was played by a man, the Living National Treasure Bando Tamasaburo V; but it was only afterwards I learned to my amazement that the actor who so convincingly portrayed the beautiful young woman, so lithe and graceful in her movements, is in his sixties.

A few days after seeing Ebizo on stage, I watched a television documentary about him. The rehearsal footage, including actors as young as three or four years old practicing dance steps, made it clear how much dedication is required to reach the pinnacle of kabuki. In one scene Ebizo had tears in his eyes as he watched a film of his father playing a role that is now his own. It clearly means a great deal to him to be the inheritor of such a great tradition. His status in Japan is similar to a movie or rock star, with newspapers eager for gossip about his private life. The weight of expectation, from both kabuki tradition and the modern media, must be enormous. Yet it is also clearly empowering, giving him a deep sense of identity and purpose.

Not many arts are as tradition-bound as kabuki, but many creators feel a sense of kinship with previous generations of creators. We draw inspiration from the giants of the past, and inherit from them themes, craft skills, artistic forms, and other traditions. I was recently reading about the Earl of Surrey, a proud Tudor nobleman who was the last man executed by Henry VIII, and who is credited as the originator of blank verse and the “English” or “Shakespearean” sonnet form. I don’t have much else in common with him, but whenever I use these forms in my own poetry, I can’t help thinking of him and the sense of excitement and pleasure he must have felt at his discoveries.

Scene from the Kabuki play Yoshitsune Sembon Zakura, via Wikimedia

Tradition does not exclude innovation. Even in the custom-bound world of kabuki there is scope for novelty. Ichikawa Ennosuke III is famous for extending the tradition of keren (stage tricks) with 20th century technology, such as his trademark flights over the audience, suspended from wires. Naturally he has attracted criticism from the more conservative quarters of the kabuki world, but he has also drawn many new fans to the theater. And keren have always been part of kabuki, which originated as popular entertainment for the common people. Like many artists, Ennosuke does not slavishly follow tradition, but engages in a creative dialogue with the past.

Tips for learning from your own creative tradition

Every creative tradition is a treasure-trove of inspiration and knowledge. Unless you know what past masters have done — and why and how they did it — you are limiting the palette of creative options available to you. So if you are serious about your creative discipline, you need to learn about its history and traditions.

Run through the following list and make a note of how well you know each category within your creative field:

- Classic works

- Contemporary works

- The avant-garde

- Works from your own country

- Works from other countries

- Critical reviews and studies

Now take one of the categories you know least well and start adding to your knowledge by reading, looking, listening, learning and/or going to events — whatever it takes to become well-versed in that aspect of your field.

Find trusted sources of new material — libraries, websites, specialist shops. Make it easy by finding ways to funnel new content towards you. Subscribe to magazines, blogs, email newsletters.

Keep an eye out for “human filters” — critics, editors, bloggers, teachers, or knowledgeable friends — people who have their pulse on what’s happening right now and can recommend the good stuff.

Do not avoid works or artists you don’t like. You don’t have to like everything, but if you want to be more than a keen amateur, you need some knowledge of every aspect of your field. Even if you only confirm your negative judgment, it’s better to do this from an informed position than dismissing things without getting to know them. And you might even surprise yourself by finding some diamonds in the rough.

How the past can fuel your creativity

As you deepen your knowledge of your creative tradition, you can use it as a springboard for new directions in your own work. Here are some questions that may help you do this.

- What themes from the past can I use in my own work?

- What traditional forms (genres, verse forms, song structures, etc.) can I use?

- Who are my heroes from the past? What can I create as a tribute to them, or as a form of dialogue with their work?

- What have we lost from our creative tradition? How could I revive it and reinvent it for the modern world?

Don’t worry that your work will seem derivative or unoriginal. Treat these dialogues with the past as experiments, to be discarded if you don’t like the results. And trust that your own talent is strong enough to mark your work indelibly as your own.

How do you relate to your creative tradition?

How familiar are you with the history of your own creative discipline?

Do you ever draw inspiration from past masters?

Do you see yourself as an innovator or the inheritor of a great tradition?

Mark McGuinness is a poet and creative coach. This is an extract from Mark’s book Motivation for Creative People: How to stay creative while gaining money, fame and reputation.

I started reading mysteries when I started reading, over 50 years ago. Was Encyclopedia Brown around then? I don’t remember.

Moved on to Holmes and Watson, then Dame Agatha. Discovered Dick Francis without realizing he was famous (one of the joys of small town Texas in pre-internet days was that you could still discover a great author in the library instead of the ads.)

During an illness far from home, I found The Complete Dashiell Hammett or something like that. Devoured it.

Consumed everything Raymond Chandler wrote; read it all multiple times. Knew that if I ever wrote, it would be in reverence to Chandler, in awe of his mean streets and moral dilemmas.

Somehow managed not to know Nero Wolfe until PBS gave him to me and now I collect Rex Stout’s hard cover editions.

And recently, after getting to know Shawn Coyne over at StoryGrid.com and knowing he’d worked on the first Elvis Cole mystery by Robert Crais, I read it — and discovered that I don’t write like Chandler, so much as I write like Crais with a twist of Chandler.

And from Crais it was a single step to Michael Connelly’s Harry Bosch books: books I wouldn’t have enjoyed if I’d read them early, or come to them directly rather than the circuitous route I followed.

I shudder to think that perhaps Sue Grafton’s books (binged, a book a day for three weeks, during another illness, but at home this time) might be a step or two away from cat mysteries.

Do I really have to read cat mysteries?

But I understand your point. I write for an audience with gentler sensibilities. I want complex people, but less graphic detail. I know the cozy mystery has much to teach me. I won’t be revisiting Sherlock and Poirot and Miss Marple, but cat mysteries sell like sex, don’t they?

If it’s research, I don’t have to like it. But confirmation bias must be quashed if I’m going to be a professional and know my field well.

We all have to make sacrifices for our art, Joel. 😉

If I’d known that before choosing my career path…

Seriously, that’s a great survey of your field Joel. I’m sure it makes the world of difference to your own writing that you can situate it within such a rich and (ahem) mysterious fictional galaxy.

If only we’d known, eh?

Big pile of every sort of mystery imaginable on the table behind me. I do so love libraries. I’d forgotten already where this whole idea came from, ungrateful wretch that I am, so thanks again.

Another bit I hadn’t thunk of: I do my own covers, and these are a trove of ideas (both to avoid and to adopt.) (More parens — did you know there’s a subgenre of coffee shop mysteries, and a subsubgenre of coffee shop mysteries set in Wisconsin? I think I’ll head downtown to Badger Brew and stir up trouble.)

For those I left on tenterhooks regarding Encyclopedia Brown, yes, the first book came out in 1963, and since I came out in ’59 the timeline works.

Great post -Thank you! It inspired my blog post which is already in the comments.

Be well, Mark!

-Mike

Thanks Mike!