In the last post we looked at the converging economic forces that make creativity a hot property in the 21st century. Mature economies such as the US, Europe, and Japan, which previously shifted from manufacturing to knowledge work, are now relying more and more on creative work.

So people like Lou are having to update their c.v.s while people like Jack and Marla are in such demand they no longer need a c.v.

These changes have given rise to the idea of the creative economy.

The Creative Economy

One of the books that inspired me to specialise in consulting in the creative sector was The Creative Economy by John Howkins, in which he identifies creativity as central to the emerging 21st century global economy.

The creative economy consists of the transactions in … creative products. Each transaction may have two complementary values, the value of the intangible, intellectual property and the value of the physical carrier or platform (if any). In some industries, such as digital software, the intellectual property value is higher. In others, such as art, the unit cost of the physical object is higher.

(John Howkins, The Creative Economy)

So the physical components of a DVD, laptop or Picasso are of trivial value compared to the intellectual property value of the film, design or art they embody. This means that the economic potential of the creative economy is enormous.

While data and knowledge are important resources, the creative economy represents a significant development from the familiar idea of the knowledge economy:

Today’s economy is fundamentally a Creative Economy. I certainly agree with those who say that the advanced nations are shifting to information-based, knowledge-driven economies… Yet I see creativity… as the key driver. In my formulation, ‘knowledge’ and ‘information’ are the tools and materials of creativity.

(Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class)

The key difference is that in the creative economy it is not enough to store, process or analyse information – it must be creatively transformed into something new and valuable.

The Creative Industries

John Howkins describes the creative economy as consisting of 15 creative industries, including advertising, architecture, design, film, music, publishing, R & D, television and video games. In 1998 the UK government came up with this definition of the creative industries, when it identified them as critical to the country’s economic future:

[The creative industries are] those industries which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and which have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property.

(1998 Creative Industries Mapping Document, UK Department for Culture, Media and Sport)

One problem with this definition is that it could apply to any industry, since it’s hard to think of an industry that does not rely on creativity, skill and talent; and copyright, trademarks and patents are becoming more prominent in a wide range of industries. According to creative industries expert Chris Bilton the creative industries cannot be divorced from the ‘old economy’ which often provides ‘the labour and the material components’ for ‘the glamorous world of creativity and culture’ (Management and Creativity).

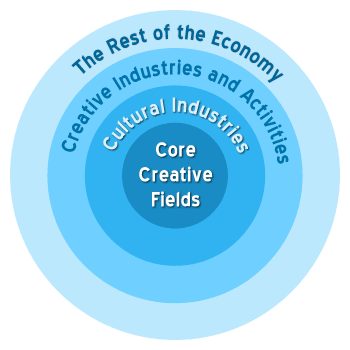

So some writers stress the differences between the creative industries and other industries, while others emphasise their similarities and connections. A recent report by the Work Foundation shows the creative economy as a series of concentric circles, with creative content producers at the core, surrounded by industries in which creativity plays a less prominent role.

The Creative Class

There are other ways of defining the creative economy. Richard Florida describes it in terms of the people employed in creative occupations—what he calls the creative class.

The economic need for creativity has registered itself in the rise of a new class, which I call the Creative Class. Some 38 million Americans, 30 percent of all employed people, belong to this new class. I define the core of the Creative Class to include people in science and engineering, architecture and design, education, arts, music and entertainment, whose economic function is to create new ideas, new technology and/or new creative content. Around the core, the Creative Class also includes a broader group of creative professionals in business and finance, law, health care and related fields.

(The Rise of the Creative Class)

When I asked Jack whether he considered himself a member of the ‘creative class’ he looked surprised. ‘I’ve never thought about it like that,’ he said, ‘I guess I don’t think of myself as part of a class, it sounds a bit old-fashioned.’

Not everyone will be comfortable with the idea of a creative ‘class’. For one thing, creative people like Jack love to see themselves as unique individuals rather than members of a crowd. And Florida confronts the issue of elitism head on, describing a widening income gap between those employed in creative professions and the service workers who support them.

But the economic reality he describes is that if you are a creative worker in the 21st century, whether in the arts, science, or business, then your talent makes you highly desirable – and opens up the possibility of spectacular creative and commercial success.

Marla said she’d read The Rise of Creative Class when it came out. ‘Professor Florida’s definitely onto something. I don’t agree with everything he says but he’s real sharp. And pretty cute.’

The Value of the Creative Economy

Measuring the value of the creative economy is not easy and depends on which definition you adopt. However it is already a significant proportion of the world economy, particularly in the more developed areas. The following estimates are from the Work Foundation report, based on figures published in 2004 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development:

The global market value of industries that rely heavily on creative and cultural inputs is estimated at $1.3 trillion according to UNCTAD figures… while the OECD points to annual growth rates of between 5 per cent and 20 per cent in its countries’ creative and cultural industries. As high value added, knowledge-intensive sectors and with real disposable income rising globally, the demand for goods and services produced by the creative industries is anticipated to rise further, fuelling growth in these sectors. [Emphasis added.]

When I asked Lou what he thought of the creative economy he said ‘Show me the numbers’. So I showed him these numbers and he went very quiet.

Brave New World or Castles in the Air?

Some enthusiasts have heralded the creative economy as a Brave New World of opportunity, a weightless wonderland of the imagination, where wealth can be conjured out of thin air. Yet in spite of the marvels of digital technology, many creative industries still require real people in real factories to produce real products.

Even at the conceptual stage, creative work involves more perspiration than inspiration. According to Richard Florida, the creative class works very long hours. Just ask Jack and Marla – they may not spend all day chained to their desk like Lou, but even when they are relaxing on holiday they have a notebook with them to jot down ideas and work on them in odd moments.

Another limitation of the creative economy comes from the highly subjective value of creative products. Remember the last argument you had with a friend about music or films. How come they couldn’t appreciate the genius of one of your favourite masterpieces? And how come they spend so long watching or listening to rubbish? These differences of opinion make creative products highly volatile. Just ask anyone who has invested a fortune in a high profile movie that flopped. The dot com crash is (so far) the most spectacular demonstration of this volatility, often cited by those who criticise the new economy as pie in the sky.

In reality the creative economy is neither a panacea nor a mass delusion but somewhere in between. The opportunities are balanced by dangers. Chris Bilton concludes that the creative economy is important ‘not because it represents a bright new future, but because it represents a future of uncertainty and risk’.

So how can we navigate this uncertain future? That’s what we’ll look at in the next post.

About the Author: Mark McGuinness is a poet and creative coach.

Interesting point about the volatility of creative products. I never thought of that before.

I think a good way to lessen the volatility is to build a repeat customer base that are fans of your work.

Also, building relationships with social media influencers like popular bloggers can help. Whenever you create a new product, you can ask them to blog about it. Their recommendation posts usually lead to a lot of sales.

Thanks Dee, good suggestions.

Re the bloggers – they won’t necessarily say good things about your product, but any criticisms (in their posts and comments from their readers) will give you valuable feedback you could use to improve the product.

What a reassuring post! I get everything from confused stares to “when’s this guy gonna grow up?” sighs when I tell people I’m a writer. It seems like no matter how many people enjoy my writing or how much money I make from it, I’m thought of as “that guy without a real job.” I don’t take much of it to heart, but it can be irritating.

Posts like these are excellent vindication for members of the creative class.

Thanks Jay – vindication is sweet. 🙂

Great site, guys!

Just to clarify – ALL valuations of products, services or whatever are subjective. It makes no difference how much it cost to make it, what it can do, what it looks like etc. All that matters is how a person values the product/service/whatever. How I see/perceive the subject at hand.

After all – we are all unique. And that’s what makes this world and life so interesting! 🙂

ps: Oh, and the dotcom bust was a result of (bad) monetary policy. Just like the existing credit crunch.

Good luck!

Thanks Reinis – re subjective value, we’re getting into deep philosophical waters here! I agree that the value of all products is ultimately subjective, although many of them have a fairly obvious practical use. E.g. a spade or a helicopter delivers an obvious practical benefit to the user. The argument about creative products is that the value resides chiefly in the symbolic content rather than any practical utility. But as you point out, it’s a matter of degree rather than any absolute distinction. Glad to hear we can blame Lou for the dot-com bust as well as the credit crunch. 🙂

Yes, the question of value is more philosophical than empirical. And many problems could have been avoided if this simple truth – that we all value things differently – had been understood. But this is actually a question of economics. 🙂

Oh well, poor Lou – it’s a hard burden for one person. 🙂

Hey, but I absolutely love your three characters. And I have an idea that you could use – create (inspirational, motivational) wallpapers with your three characters and their quotes.

I’m thinking something like this: http://anabubula.com/content/Motivational-wallpapers-001

Thanks for the idea, I’ll see what Tony thinks of it.

Great idea, Reinis.

We’ve also been asked about shirts and stuff. It’s definitely something we’ll do if there is enough interest.