This article is about a moment in time that changed the course of Western civilisation forever.

This article is about a moment in time that changed the course of Western civilisation forever.

An era that began a new way of thinking. When imagination flourished and artists were thought to be near divine beings. A time when humankind experienced a glorious rebirth.

This new movement promised freedom from the plagues, disease and death so common in the middle ages. Freedom from dogmatic inflexible traditions under which people were horribly oppressed.

Humanity was leaving a period of darkness and confusion behind, coming into the colour and light of the Renaissance period.

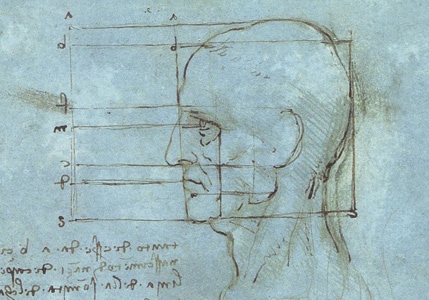

One of the most prominent artists of the time was Leonardo da Vinci, born on the 15th April 1452. He turned the artist from craftsman to genius – primarily because his paintings depicted not only physical appearances but, for the first time, intrigue, feelings and inner states of mind. He also did outstanding work as an architect, scientist, inventor, mathematician, engineer, anatomist and geologist.

But the lessons of Leonardo and his time are not confined to the history books – here’s what they have to teach modern artists and creators.

1. New knowledge brings new creative possibilities

During the Renaissance intricate knowledge of human anatomy was revealed. Perspective was discovered. Classical sculpture was rediscovered. New painting techniques developed. Heavenly music was composed. And majestic architecture was built.

Artists changed the world by applying this knowledge and combining it with their imagination – as well as vast wealth from powerful Italian families such as the Medici.

Lesson 1: Future historians will look upon our ‘information age’ as another significant breakthrough in the history of humankind. Take full advantage of the opportunity to increase your creative potential by acquiring meaningful knowledge.

2. Align yourself with power

Leonardo was a bastard child of a poor farm girl. He had no formal education and learnt to fight for his survival.

The infamous Medici held great power in Florence at the time. Life was cheap and executions commonplace. Leonardo knew he needed to become a member of the famous guilds to succeed in life.

But it was incredibly rare for an illegitimate child to rise above his natural born status and become successful, let alone become an established household name and revered artist amongst high society.

Leonardo understood the importance of mixing in the right circles.

Early in his teenage years he travelled to the big city of Florence. There he intermingled with the best minds and most successful artists in the country, taking an apprenticeship in the renowned studio of Andrea del Verrocchio.

However, Leonardo quickly outshone his teacher and was honoured at the age of twenty, by being accepted into the highly esteemed Painters’ Guild of Florence. This public elevation gave him instant access to the most powerful and influential people in Italy.

Lesson 2: Improve your chances of success by networking and aligning yourself with people who are already powerful and successful.

3. Don’t hide your light under a bushel

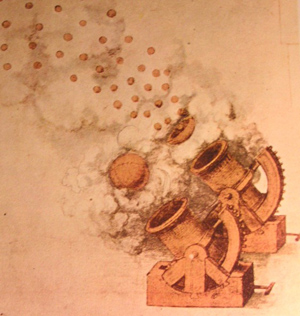

He signed his letter to the king as “a genius designer of weapons in war”. In fact, most of Leonardo’s military ideas were not to be used until 400 years later, when his drawings inspired the tanks of the First World War.

In his letter, da Vinci boldly offered his instruments of war to the Duke, full of ideas that had never been thought of before. He tempted His Excellency by saying “I can construct bridges… I can demolish every fortress… I can make a cannon… I can make armoured wagons that carry artillery”.

As if that were not enough, in a side note he added “I can further execute sculpture in marble, bronze or clay, also in painting I can do as much as anyone else”. He concluded the letter by challenging the Duke: “If any of these things seem impossible or impractical, I offer myself ready to make a trial and prove myself worthy.”

Lesson 3: Promote your ideas and your work with boldness and self-confidence. If you don’t believe in them enough to speak up for them, who will?

4. Perfectionism sabotages even the greatest artists

Leonardo was a restless artist who struggled to finish paintings. His perfectionism meant that he would lose his passion for the work in hand and turn his genius towards something completely different. His mind needed constant stimulation away from his art. Da Vinci focussed upon a variety of diverse major projects during his lifetime ranging from human anatomy, geology, town planning, even man-powered flight.

This recurring trait caused great frustration for kings and paymasters at the time. In the centuries after his death, few have ventured to doubt his abilities – but quite a few have criticised the fragmentary nature of much of his work.

Lesson 4: Strive for excellence, but accept that imperfection is unavoidable as a human being. Finish what you start, even if it falls short of your vision.

5. Solitude is essential for creativity

Although charming and attractive, commanding everyone’s affection, Leonardo valued his time alone saying:

Alone you are all yourself, with a companion you are half yourself.

But it was during his many hours spent in solitude, generating ideas and drawing in his sketchbook, that da Vinci was most creative.

Lesson 5: Build in quiet time – for reflection and focused work – during your day. Remember the power of introverts!

6. Experimentation comes at a price

But Leonardo’s experimentation with paint on the masterpiece failed miserably. Dampness in the wall began to disintegrate the frescoe and the paint faded considerably.

The painting we have today is a pale shadow of its freshly-painted glory. Leonardo often tried creative ways to accomplish his lofty goals in painting, but even this creative genius came unstuck.

Lesson 6: Experiment on preliminary sketches or prototypes only. Be sure to use high quality materials for long lasting results in the final piece.

7. Power shifts unpredictably and fast

Desire for status, influence and a driving ambition to succeed captured Leonardo’s heart. He knew how the world worked in the noble courts of kings and he played the game well. However, the fickle nature of Italian politics and the transience of power was strikingly real for an artist in this time.

As kings toppled, so did artistic patronage.

Many times Leonardo’s source of income dried up. He was accustomed to rejection and often found himself out of favour with powerful authorities. He eventually left Milan a broken man, abandoning his Last Supper masterpiece and other famous commissioned works.

Lesson 7: Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. If you’re an employee, build your reputation in the industry, in case you ever need a new position; if you’re a freelancer, don’t rely on one or two clients; if you’re a creative entrepreneur, develop multiple income streams.

8. Leave a legacy you can be proud of

Leonardo climbed from poverty to achieve high status in society. Shortly after his 67th birthday he passed away and the world lost an astoundingly brilliant and diverse creative mind.

According to legend, Leonardo died in the arms of the King of France. He is recorded to have said “as a well spent day brings happy sleep, so life well used brings happy death”.

Lesson 8: Don’t be satisfied with ‘good enough’ or just keeping clients happy. Challenge yourself to create amazing work that will stand the test of time.

Images from Wikimedia Commons: Leonardo, Head, Cannon, Last Supper, Plant.

About the Author Simon Brushfield is an Australian abstract artist whose work has been described as “poetic, enigmatic and dreamlike” (Michael Berry, Selected Contemporary Artists of Australia). His paintings have been exhibited and sold across Australia and Asia and collected by private and corporate clients in Europe and America. For more information visit SimonBrushfield.com.

Wonderful piece, Simon. Worth book marking for regular review.

#4 raised a surprising thought: was perfectionism really a problem for Leonardo? Is it really a problem for us?

I understand, even preach, the wisdom of finishing, shipping. I wonder, though, whether the frustrating unfinished works weren’t the experimentation, the respite, the fuel for those which were finished.

Not suggesting I have a clue to the answer, but the question itself surprised me when it entered my head.

You know, as I read that part I was thinking about another of my favourite creators – Coleridge. Like Leonardo, he had many interests and left several unfinished masterpieces behind. One critic called him the “master of the suggestive fragment”, while others have castigated him for leaving so much of his promise unfulfilled.

They both strike me as very human artists – aspiring to the divine, touching it at times, but also falling short.

“aspiring to the divine”

Precisely. Those who do so but fall short inspire me so much more than those who aim for less and succeed.

Thanks Joel, glad you liked it. It is comforting for me to know such great figures in the history of mankind were just as human as I am. Quite amazing really. They must have got out of bed some mornings and had bad hair days just like us. As Mark alludes, it’s easy to forget the fact we are all common human beings. But maybe that’s exactly where the divine resides?

Wonderful post. I especially like the cautionary lessons.

So pleased you liked it Lisa. I always love art history and read it for inspiration. There is so much to learn from such a rich artistic heritage at our fingertips. I think guys like Leonardo would be happy to know we’re still learning centuries later from his amazing life.

Enjoyed the post, thank you Simon. I like you’ve written it as a learning tool.

When you mentioned the part about perfectionism it struck a chord … there is a commission that I have been struggling to finish for … well I’m not going to tell you, it’s embarrassing … i’ll just say too long! Luckily one of the little girls in the painting has studied Leonardo at school and told her mummy that it’s really quite usual to take so long as Leonardo frequently did!! … when I work I follow my impulse and do not think about what I am doing and I will admit I have been diverted elsewhere on this one and moving to finish it is proving a little challenging. This doesn’t always happen, but once in a while it does …

I didn’t realise it but I think that I was feeling a little bad about this deep down … and your article has help me feel better about it, thank you. Maybe I will succeed in finishing it now ….

We can only do our best …

Hi Liz, Thanks so much for your comments, very brave to expose your honest thoughts like that. It really makes me happy to hear the article has helped you progress in your creativity.

People with a curious creative mind like us and DaVinci are easily diverted. I believe this curiosity is what helps make great art. But like you said, if left unchecked it can send us into a circle of unproductive thinking. Whatever the reasons why, it’s great that you have recognized the problem.

Who knows, maybe you needed that space and time away from the artwork?

I bet now you will go ahead and create an amazing work of art. I hope so. Trust your creative impulse – it knows what’s right. Yes, we can only do our best in life. Like Leonardo said, “as a well spent day brings happy sleep, so life well used brings happy death.”

I’d say yes, space away from paintings is just as important as space with it. I’ll keep you posted on how I do with this one Simon … until then, enjoy much happy sleep :o)

Brilliant article, Simon. Leonardo is one of my all time artistic heros. And yet he seemed almost to be cursed by his overabundence of creative ideas. Though his paintings are what the world most famously remembers him for, it was his military weaponry ideas and large scale civil engineering plans that he always sought out commissions for but never really received his due in his lifetime.

It’s like the modern equivalent to the well paid copywriter telling his friends and colleagues ‘but what I really do is write fiction.’

I’m as guilty as they come for starting one creative endeavor and jumping to the next before completing it.

It’s all too easy to get caught up in the day to day struggle to just get by, making something that gets us another client or more work. But thinking in terms of your legacy, of your life’s work, of doing something truly great and memorable, this alludes so many of us and yet it’s such an important point to keep in mind for the creative.

Thanks for a great reminder that greatness does not come without a price.

Thanks Mark, I really appreciate your comments and like your modern equivalent to a well paid copywriter idea. Many people operate as you say – ‘this is what I really do’. But if we can begin to integrate the two worlds and be bold like Leonardo, I believe creative people would be much happier waking up for work everyday. Taking mild risks is one key in my life. It helps me take small steps everyday towards the bigger goal. Which means over time, I give myself a greater chance that ‘it’ will become a reality. Then one day in the future we’ll find ourselves ‘really doing what we really do’ 100% – and loving it! But even then, we will have something else exciting to strive for. Many creative people have a restless mind like Leonardo. It’s a never ending cycle taking us higher and higher. The process itself is a life long steady goal towards seeking excellence. Which will undoubtedly create a valuable legacy for others to enjoy.

I enjoyed your article very much. I am an aspiring artist and I always come back to Leo to try and grasp his depth. It was part work, part extreme capacity and use of his mind. He was a wonderful human being.

I wanted to note to you that one thing you said was not entirely correct. Leonardo Da Vinci did not have to scrape by because of his mother. He was raised in his fathers home. His mother was somewhere else.

I appreciate your use of his qualities, nice work!