Considering I’m a creative coach, some people are surprised to learn I’m a little sceptical about creative thinking techniques.

For one thing, there’s a lot more to creativity than thinking. It’s possible to sit around having lots of creative thoughts, but without actually making anything of them. But if you start making something, creative ideas seem to emerge naturally out of the process. So if I had to choose, I’d say creative doing beats creative thinking.

And for another thing, a lot of ‘creative thinking techniques’ leave me cold. Brainstorming, lateral thinking and thinking outside the box have always felt a bit corporate and contrived to me. I’ve never really used them myself, and after working with hundreds of artists and creatives over the last years, I’ve come across plenty of other creative professionals who don’t use them. I don’t think you can reduce creative thinking to a set of techniques. And I don’t think the process is as conscious and deliberate as these approaches imply.

Having said that, here are four types of creative thinking that I use myself and which I know for a fact are used extensively by high-level creators. Only one of them (reframing) is under conscious control. Another (mind mapping) works via associative rather than rational thinking. And the other two require us to let go of our logical, analytical mind and open up to whatever inspiration visits us from the unconscious mind.

The text below introduces the four types of creative thinking, and the worksheet will show you how to apply the techniques to your own work.

1. Reframing

Image by stuartpilbrow

Reframing opens up creative possibilities by changing our interpretation of an event, situation, behaviour, person or object.

Think about a time when you changed your opinion of somebody. Maybe you saw them as ‘difficult’ or ‘unpleasant’ because of the way they behaved towards you; only to discover a reason for that behaviour that made you feel sympathetic towards them. So you ended up with an image of them as ‘struggling’ or ‘dealing with problems’ rather than bad.

Or how about a time when you were pleased to buy something at a very low price, only to be disappointed when it broke the first time you used it? In your mind, it went from being a ‘bargain’ to ‘cheap rubbish’.

Or what about a time when you experienced a big disappointment, only to discover an opportunity which emerged from it? As the old saying goes, ‘when one door closes, another opens’.

All of these are examples of reframes, since the essential nature of the person, object or event didn’t change — only your perception of them. When you exchanged an old frame for a new one, things looked very different.

Jokes depend on reframing for their humour. The punchline is the moment when one frame is substituted for another, wildly incongruous or inappropriate frame. For example, when Homer Simpson says “Maybe, just once, someone will call me ‘Sir’ without adding, ‘You’re making a scene'”, it’s funny because of Homer’s swift transition from respected gentleman (high status frame) to embarrassing troublemaker (low status frame).

I first came across reframing when I trained as a psychotherapist. As a therapist, I met lots of clients who were unhappy for good reasons, but I also discovered that many of them were making themselves even more miserable with the interpretations (frames) they put around their life events. Part of my job was to offer them new frames that fitted the facts just as well, but allowed them to feel better about themselves and find creative solutions to the problems they faced.

For example, a single mother feeling overwhelmed by the challenges of keeping down a job and taking good care of her children could cheer up considerably when I suggested that she wasn’t a ‘bad mother’ (negative frame) but ‘coping very well in difficult circumstances’ (positive frame).

Many outstanding creators make extensive use of reframing, finding new possibilities where others see obstacles. As advertising Creative Director Ernie Schenck puts it: “You see a wall, Houdini saw an opening.” (The Houdini Solution)

What reframing does to your brain

In his excellent book Your Brain at Work, David Rock explains the powerful impact reframing — which he calls reappraisal — can have on your brain, quoting neuroscientist Kevin Ochsner:

Our emotional responses ultimately flow out of our appraisals of the world [i.e. frames], and if we can shift those appraisals, we shift our emotional responses.

(Kevin Ochsner, quoted in Your Brain at Work by David Rock)

So reframing isn’t just an intellectual exercise – it changes the way we feel, which in turn changes our capacity for action. Which makes it a powerful creative tool for changing our own lives and influencing other people.

Creative frames of reference

Here are some frames to help you generate creative solutions. Next time you’re facing a creative challenge or are stuck on a problem, run through this list and ask yourself the questions. Once you’ve done this a few times, you should get into the habit of asking yourself these questions, and making creative use of reframing.

- Meaning — what else could this mean?

- Context — where else could this be useful?

- Learning — what can I learn from this?

- Humour — what’s the funny side of this?

- Solution — what would I be doing if I’d solved the problem? Can I start doing any of that right now?

- Silver lining — what opportunities are lurking inside this problem?

- Points of view — how does this look to the other people involved?

- Creative heroes — how would one of my creative heroes approach this problem?

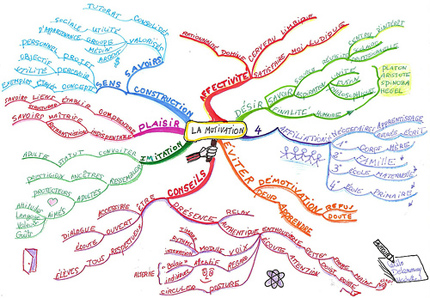

2. Mind mapping

Image by Philippe Boukobza

When you make notes or draft ideas in conventional linear form, using sentences or bullet points that follow on from each other in a sequence, it’s easy to get stuck because you are trying to do two things at once: (1) get the ideas down on paper and (2) arrange them into a logical sequence.

Mind mapping sidesteps this problem by allowing you to write ideas down in an associative, organic pattern, starting with a key concept in the centre of the page, and radiating out in all directions, using lines to connect related ideas. It’s easier to ‘splurge’ ideas onto the page without having to arrange them all neatly in sequence. And yet an order or pattern does emerge, in the lines connecting related ideas together in clusters.

Because it involves both words and a visual layout, it has been claimed that mind mapping engages both the left and right hemispheres of the brain, leading to a more holistic and imaginative style of thinking. A mind map can also aid learning by showing the relationships between different concepts and making them easier to memorize.

Visual approaches to generating and organising ideas have been used for centuries, and some pages of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks are often cited as the inspiration for modern mind maps. Tony Buzan is the leading authority on mind mapping. Among his tips for getting the most out of the technique are:

- Start in the centre of the page

- The lines should be connected and radiate out from the central concept

- Use different colours for different branches of the mind map

- Use images and symbols to bring the concepts to life and make them easier to remember

For more tips on mind mapping, as well as books and software tools, visit Tony Buzan’s website.

3. Insight

The word insight has several different meanings, but in the context of creative thinking it means an idea that appears in the mind as if from nowhere, with no immediately preceding conscious thought or effort. It’s the proverbial ‘Aha!’ or ‘Eureka!’ moment, when an idea pops into your mind out of the blue.

There are many accounts of creative breakthroughs made through insight, from Archimedes in the bath tub onwards. All of them follow the same basic pattern:

- Working hard to solve a problem.

- Getting stuck and/or taking a break.

- A flash of insight bringing the solution to the problem.

The neuroscience of insight

Recent research by neuroscientists has validated the subjective descriptions given by creators. It has also thrown up some interesting discoveries.

Although it may look (and even feel) as though you are doing nothing in the moments before an insight emerges, brain scans have shown that your brain is actually working harder than when you are trying to reason through a problem with ‘hard’ thinking:

These sudden insights, they found, are the culmination of an intense and complex series of brain states that require more neural resources than methodical reasoning. People who solve problems through insight generate different patterns of brain waves than those who solve problems analytically. “Your brain is really working quite hard before this moment of insight,” says psychologist Mark Wheeler at the University of Pittsburgh. “There is a lot going on behind the scenes.”

(A Wandering Mind Heads Towards Insight by Robert Lee Hotz)

So if anyone accuses you of being idle next time they see you staring out the window or strolling in the park, point them to the research!

Neuroscience has also revealed that the right hemisphere of the brain — long associated with holistic thinking, as opposed to the more logical left hemisphere) — is strongly involved in the production of insights. Another finding is that you are more likely to have an insight when you feel happier than when you feel anxious. So maybe suffering for your art isn’t such a good idea after all!

According to David Rock, self-awareness is a key to unlock insight. It’s important to recognise when you get stuck on a problem and instead of trying to push through it by working harder, deliberately slow down, calm your mind and allow your thoughts to wander. Rock also points out that every insight comes with a burst of energy and enthusiasm that helps you put it into action.

How to have an insight

In a book published over fifty years ago, advertising copywriter James Webb Young outlined A Technique for Producing Ideas which dovetails neatly with the accounts of creators and the discoveries of modern neuroscience. He describes his own practice in coming up with ideas for advertisements, which he distils into a four step sequence:

- Gathering knowledge — through both constant effort to expand your general knowledge and also specific research for each project.

- Hard thinking about the problem — doing your best to combine the different elements into a workable solution. Young emphasises the importance of working yourself to a standstill, when you are ready to give up out of sheer exhaustion.

- Incubation — taking a break and allowing the unconscious mind to work its magic. Rather than simply doing nothing, Young suggests turning your attention “do whatever stimulate your imagination and emotions” such as a trip to the movies or reading fiction. (Remember what the neuroscientists say about being happy rather than anxious.)

- The Eureka moment — when the idea appears as if from nowhere.

- Developing the idea — expanding its possibilities, critiquing it for weaknesses and translating into action.

As well as being clear, practical and a charming relic of the classic age of advertising, Young’s book has the added virtue of being short and to the point (48 pages).

A word of warning: don’t let incubation become an excuse for laziness! Read my article on the difference between incubation and procrastination if you want to wipe out that particular excuse. 🙂

4. Creative flow

You know that feeling you get when you’re completely absorbed in your work and the outside world seems to melt away? When everything seems to fall into place, and whatever you’re working with — ideas, words, notes, colours or whatever — start to flow easily and naturally? When you feel both excited and calm, caught up in the sheer pleasure of creation?

I have some good news for you. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmahalyi has studied this state — which he calls creative flow — and concluded that it is very highly correlated with outstanding creative performance. In other words, it doesn’t just feel good — it’s a sign that you’re working at your best, producing high-quality work.

Csikszentmahalyi has described nine essential characteristics of flow:

- There are clear goals every step of the way. Knowing what you are trying to achieve gives your actions a sense of purpose and meaning.

- There is immediate feedback to your actions. Not only do you know what you are trying to achieve, you are also clear about how well you are doing it. This makes it easier to adjust for optimum performance. It also means that by definition flow only occurs when you are performing well.

- There is a balance between challenges and skills. If the challenge is too difficult we get frustrated; if it is too easy, we get bored. Flow occurs when we reach an optimum balance between our abilities and the task in hand, keeping us alert, focused and effective.

- Action and awareness are merged. We have all had experiences of being in one place physically, but with our minds elsewhere — often out of boredom or frustration. In flow, we are completely focused on what we are doing in the moment. Our thoughts and actions become automatic and merged together — creative thinking and creative doing are one and the same.

- Distractions are excluded from consciousness. When we are not distracted by worries or conflicting priorities, we are free to become fully absorbed in the task.

- There is no worry of failure. A single-minded focus of attention means that we are not simultaneously judging our performance or worrying about things going wrong.

- Self-consciousness disappears. When we are fully absorbed in the activity itself, we are not concerned with our self-image, or how we look to others. While flow lasts, we can even identify with something outside or larger than our sense of self — such as the painting or writing we are engaged in, or the team we are playing in.

- The sense of time becomes distorted. Several hours can fly by in what feels like a few minutes, or a few moments can seem to last for ages.

- The activity becomes ‘autotelic’ – meaning it is an end in itself. Whenever most of the elements of flow are occurring, the activity becomes enjoyable and rewarding for its own sake. This is why so many artists and creators report that their greatest satisfaction comes through their work. As Noel Coward put it, “Work is more fun than fun”.

Worksheet

Podcast episodes

The following episodes of The 21st Century Creative Podcast touch on the themes of today’s lesson:

The Floatation Tank – a Short Cut to Your Superpower? with Nick Dunin

Other resources

Written by me, unless otherwise indicated

Creative Thinking

A Whack on the Side of the Head: How You Can Be More Creative by Roger von Oech. My favourite book on creative thinking – witty, provocative, playful and memorable.

Thinkertoys: A Handbook of Creative-Thinking Techniques by Michael Michalko. Superb compendium of creative thinking techniques.

Creativethinking.net – Michael Michalko’s website, featuring lots of free tools and techniques.

Is Lateral Thinking Necessary for Creativity?

Is Brainstorming a Waste of Time?

1. Reframing

Are You Trapped in Black-and-White Thinking? (Includes a cool optical illusion.)

The Houdini Solution: Put Creativity and Innovation to Work by Thinking Inside the Box by Ernie Schenck. Starts by inverting (reframing) conventional assumptions about the need to think outside the box to be creative. A brilliant and unconventional account of the creative process by an award-winning creative director.

Why Thinking Outside the Box Doesn’t Work

Spark Your Creativity By Thinking INSIDE the Box

Creative Constraints: How to Use Them and When to Lose Them

Your Brain at Work by David Rock. Chapter 8 covers the neuroscience of reframing (called ‘reappraisal’ in the book).

2. Mind Mapping

The Mind Map Book: Unlock Your Creativity, Boost Your Memory, Change Your Life by Tony Buzan

3. Insight

What’s the Difference Between Incubation and Procrastination?

A Wandering Mind Heads Towards Insight by Robert Lee Hotz

A Technique for Producing Ideas by James Webb Young

Your Brain at Work by David Rock. Chapter 6 covers the neuroscience of insight.

4. Creative Flow

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi – Does Creativity Make You Happy?

Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Fascinating book which looks at several aspects of creativity, including creative flow.

Is Writing Fun? by Steven Pressfield

Tune in next week …

… when we’ll look at what you can do if you experience that most embarrassing of problems for a creative professional — a creative block.

About The 21st Century Creative

Copyright © Mark McGuinness 2010-2019