Because materials were expensive and skilled artisans were relatively rare, and there was no mass media to boost profits via economies of scale, only the clergy and nobility could afford to commission artworks – and their tastes were pretty conservative.

Walk around the medieval section of the National Gallery in London, and a lot of it is a bit samey – endless Madonnas and crucifixions. Lots of halos and gold leaf. Holy people looking pious.

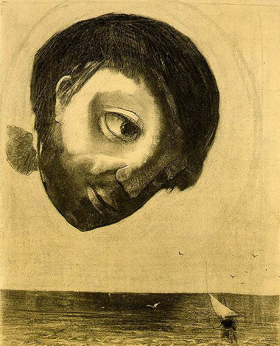

Hell makes a refreshing change – looking at some of the orgies and mutilations, you get the sense that the artists were relieving a lot of pent-up frustration.

Later on, things livened up when ignoble layfolk grew wealthy enough to buy pictures – landscapes, portraits, battles and some weird and wonderful stuff from classical mythology.

But it wasn’t until the late nineteenth century that we start to see seriously experimental works, expressing a distinctively individual personality and worldview. Enter the Bohemians and outsiders, proudly aloof from mainstream society and fiercely critical of ‘bourgeois’ tastes.

Yet it’s ironic that the market forces they despised helped to create an environment in which their work could flourish.

Vincent van Gogh was the archetypal tortured, starving artist. Yet economist Tyler Cowen points out that the capitalist system that made him an outsider also helped to make his art possible:

Falling prices for materials have made the arts affordable to millions of enthusiasts and would-be professionals. In previous eras, even paper was costly, limiting the development of both writing and drawing skills to relatively well-off families. Vincent van Gogh, an ascetic loner who ignored public taste, could not have managed his very poor lifestyle at an earlier time in history. His nonconformism was possible because technological progress had lowered the costs of paints and canvas and enabled him to persist as an artist.

(Tyler Cowen, In Praise of Commercial Culture

)

This trend continued into the twentieth century – the more costs fell, the less constrained artists were by the need to sell to the rich or the mass-market, and the freer they were to express their own idiosyncratic vision. In Cowen’s words, “modern art became possible”.

It’s a similar story in other art forms – as time has gone by, the cost of materials has fallen, living standards have risen, and creators have had to pander less and less to the conservative tastes of the establishment or the bourgeois tastes of the masses.

And the internet has accelerated the trend recently, making it possible for anyone with a laptop and an internet connection to find an audience for their work.

So what does this mean for you?

Firstly, none of us creates in a vacuum. Like it or not, economic forces exert a powerful influence on the conditions in which we work.

Secondly, these days you don’t need to be rich, or to please the rich, to do amazing creative work. The tools are at your disposal.

Thirdly, with a little effort and imagination you can find an appreciative audience for your work, however weird or off-the-wall it may look to the viewers of Fox News or readers of the Daily Mail. Maybe there are only a handful of people in your home town with similar tastes to you – but if you multiply that handful by the number of hometowns on this planet, you could fill a stadium several times over.

Fourthly, if you want to earn a living from your creative work, you need to devise a sustainable system – in which you are not only meeting the cost of living and your materials, but also earning enough to feed your imagination with better tools, art, music, literature and/or gigs and exhibitions – as well as inspiring experiences.

It’s a tricky balancing act, but if you want to create avant-garde artwork, provide an ultra-niche service, or build a radically innovative company, there has never been a better time in history than right now.

Over to You

How important is it for you to follow your own creative vision vs provide something that appeals to a mass market (or rich corporate client)?

How do the costs of equipment and materials in your field compare with ten, twenty or a hundred years ago?

What are your favourite examples of avant-garde artists or unusual companies who stretched the limits of what was possible for their time – artistically and economically?

About the author: Mark McGuinness is a poet and a creative coach.

Here’s my take on your question regarding creative vision versus appeal: if you don’t believe in what you’re doing, the money (or the swanky clients) aren’t worth a damn.

That kind of work will eat you alive.

If there’s absolutely no market for your vision, you might have a tough decision to make. It doesn’t mean you should abandon your art, but if you want to keep a roof over your head, you have to square with that.

If there is a market, then you have to get down to it – make your very best work, show it in its best light, and reach your best buyers.

Listening to the audio seminar now. Cheap pricing = crap customers. Nodding my head.

Yep it’s a fine line to tread!

Another possibility is that there may not be a market for your core vision, but there could be one ‘next door’ to it. E.g. My main creative passion is poetry, which is a very small market (at least in financial terms) but I earn my living helping other creative people with their work, which is rewarding for me on many levels.